Ecological Consequences of Hydropower Development in Himachal Pradesh with Special Reference to Chamera Dam

Corresponding author Email: rajneesh@pu.ac.in

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.17.1.17

Hydropower is an important renewable energy resource and one of the most efficient power generation systems on the planet. Despite all of the benefits of hydropower plants, there may be some drawbacks. However, its growth is accompanied by negative environmental consequences. Hydropower dams are still being constructed at a rapid pace in the developing world and are causing disturbances to river ecology, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, increased greenhouse gases emissions, as well as displacing thousands of people and affecting their food system, water sources, and agriculture. While environmentalists around the country reject massive projects with large reservoirs, locals in Himachal Pradesh consider modest projects as a scourge as well. The steady deterioration in environmental parameters in the hills has serious connotations for sustainable development, not only for the hill areas, but for the country as a whole. The goal of this research is to look at the environmental effects of hydropower and possible mitigating strategies. In short, our aim has been to study how damming has had ecological impacts on the dislocated people, to assess their reaction, receptivity, and outlook towards the projects. The interview method was adopted for collecting data. Survey has been conducted with the help of a well designed interview schedule.

Copy the following to cite this article:

Sharma R. Ecological Consequences of Hydropower Development in Himachal Pradesh with Special Reference to Chamera Dam. Curr World Environ 2022;17(1). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.17.1.17

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Sharma R. Ecological Consequences of Hydropower Development in Himachal Pradesh with Special Reference to Chamera Dam. Curr World Environ 2022;17(1).

Download article (pdf)

Citation Manager

Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 18-12-2021 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 29-03-2022 |

| Reviewed by: |

Arpit Bhatt

Arpit Bhatt

|

| Second Review by: |

Sanchit Agarwal

Sanchit Agarwal

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr Hiren b soni |

Introduction

Development of a nation has to be people friendly as well as environment friendly. Over-exploitation and over-exhaustion of the natural environmental resources can play havoc with the development of the people as depletion of resources on this finite planet will have dangerous implications for the future generations. Besides, to improve the quality of life of people, infrastructural development such as construction of dams, canals, power energy, roads, telecommunication, airways, waterways, irrigation network, etc. is significant but this may lead to various negative outcomes, one of these being involuntary displacement of population.

Developing countries planned and are planning to establish industries, dams and other developmental projects in the rural, as well as, urban areas without taking into consideration the environmental problems associated with the misuse of natural resources like soil, water and forests. They overlook and disregard the fact that there are many intended and unintended consequences of the development processes. For instance, while treating environment as a resource, there is an imminent threat to the natural environment of the developing countries with the rapid industrialization and urbanization. Hence, there is a need of ‘sustainable development’, which implies a kind of development which can sustain ecology, as well as, conserve and preserve the existing natural resources. Brundtland commission has projected the Sustainable development as development that meets the requirements of the current generation without compromising future generations' ability to meet their own needs.

The term "environment" comprises air, water, soil, flora and fauna, societies, habitats, and livelihood, among other things, and is a complex mix of diverse inter-relationships that these components of the environment have with one another. Today's priority is not just to preserve them for the current generation, but also to ensure that they are used by future generations. The future of the people is dependent upon the present acts and actions of ours, in conserving and sustaining this benign gift of God, that is Himalayan Environment.1

The Himalaya mountains are one of the world's most vulnerable regions. They look to be powerful and intimidating, but they are weak and vulnerable in the environment, and the man-environment connection is dangerously balanced. Population growth, rapid urbanization, industrialization and the greed of man to overuse resources, have further accentuated the process of environmental degradation in the inhabited parts of Himalayas. The Himalaya has become an environmentally dangerous zone as a result of declining biota, soil erosion, and landslides caused by the loss of forest cover, and the entire hydrological cycle appears to have been disrupted.1

Himachal Pradesh and Hydropower

The state of Himachal Pradesh, which forms a part of the Western Himalaya, is environmentally fragile and ecologically vulnerable. It has been passing through a state where evaluation of environmental problems has become necessary in order to identify the entire points and suggest strategies for sustainable development, which is socially relevant, economically viable, and environmentally safe and eco-friendly.1

The Union Territory of Himachal Pradesh was elevated to the status of a full-fledged state on January 25, 1971, making it the Indian Union's 18th state. Currently, the state is divided into the following twelve districts:

1. Bilaspur, 2. Chamba, 3. Hamirpur, 4. Kangra, 5. Kinnaur, 6. Kulu, 7. Lahul-Spiti, 8. Mandi, 9. Shimla, 10. Sirmour, 11. Solan, and 12. Una.

The history of power generation in the state goes back to the year 1908 when the Chamba State under the administrative capabilities of the then Raja Sir Bhuri Singh set up a 35 K.W. D.C. hydel generating power house at Chamba. This was the first Power House in northen India and as such Chamba town had electricity much earlier than Lahore, the capital of Punjab.

Another hydro-electric power project (Chaba Project near Shimla ) in the area what comprises now the State of Himachal Pradesh was set up way back in 1912 . The then British Government initiated the Chaba Project near Shimla, to meet the requirements of this erstwhile capital of the British Raj. This was followed by commissioning of power house in Bharmour (Chamba District) in 1933 and also installing another 100 K.W. D.C. hydel generating set in Bhuri Singh Power House, Chamba in 1938 which was replaced by new 100 K.W. A.C. hydel generating set in 1957. The old 35 K.W. D.C. hydel generating set was also replaced by 100 K.W. A.C. hydel generating set by augmenting the power house, thus making the capacity of the power generation as 200 K.W. Further augmentation of Bhuri Singh power house was taken in hand in 1983 and completed in 1985 by installing a new generating unite of 250 KW by extending the existing power house building. With this augmentation the capacity of Bhuri Singh Power House has increased to 450 KW.

The Shanan Power House was built at Joginder Nagar (Mandi District), for the construction of which the Kangra railway line was laid down from Pathankot to Jogindernagar. Though in the late sixties a number of small projects were taken up, it was only after the formation of Himachal Pradesh as a full- fledged State in 1971 that systematic hydro-power development was undertaken.

The first significant dam was built at Village Pong in the Dehra-Gopipur tehsil of Kangra district in Himachal Pradesh, across the river Beas near the foothills of the Shivalik Range. The dam's construction began in 1961 and was finished in 1974. The dam's full reservoir level was 433.12 metres.

In 1975, the National Hydroelectric Power Corporation (NHPC) was formed. Over the course of its 45-year history, NHPC has grown to become India's largest organisation for hydropower development, with the ability to handle all aspects of hydropower project development, from inception to commissioning. Baira Siul Hydroelectric Project in Himachal Pradesh was the first venture to be taken up by the N.H.P.C. The Project is located in the District of Chamba. It utilizes flow of the three tributaries of the river Ravi - Baira, siul and Bhaledh. The Project construction was initially taken up in 1970 by the Central Hydroelectric Power Construction Board under Ministry of Irrigation and Power as a Central Sector Project. Subsequently, after the formation of N.H.P.C., Project was entrusted to NHPC on 21.1.1978. The project was commissioned in 1982 at a total cost of Rs.148.08 crores. The original installed capacity of the project was 180 MW. Subsequently, it has been increased to 198 MW by up-rating the capacity of each unit to 66 MW through Renovation and Modernization of the Plant during 1991-92.

The five largest rivers that run through Himachal Pradesh are the Chenab, Ravi, Beas, Sutlej, and Yamuna, which all originate in the Western Himalayas and flow through the state. These snow-fed rivers and its tributaries discharge a large amount of water throughout the year and run with high bed slopes, which are used to generate electricity. Himachal Pradesh is naturally suited for hydropower generation and accounts for around 25.9 % of India’s total hydropower potential. It has been predicted that roughly 27,436 MW of hydroelectricity power can be generated in the state by developing various big, medium, small, and mini/micro hydel projects on the state's five river basins based on preliminary hydrological, topographical, and geological investigations.

The Satluj is the state's largest river system, with a catchment area of 20,398 km2. It flows through the districts of Lahaul and Spiti, Kinnaur, Shimla, Solan, and Bilaspur before entering Punjab and flowing into the huge Bhakra dam.

The Beas formerly known as the 'Vipasa,' the Beas is the second-largest river in the country, having a catchment area of 13,663 km2. It begins near the Rohtang pass at Beas Kund. It flows 286 kilometres from north to south west before entering the Pong Reservoir and Punjab.

The Chenab, also known as the Chandrabhaga, is the world's largest river by volume. It has a 7850 km2 catchment area. At an elevation of 4891 metres, the Chandra and Bhaga originate on opposite sides of the Baralacha. Before entering Kashmir, it flows north-west.

The Yamuna is nourished by a number of tributaries before flowing into Uttar Pradesh in the south-eastern part of Himachal Pradesh.

The Ravi river rises in an amphitheatre-shaped basin in the Dhauladhar Range and flows southwards through the Dhauladur Hills, carving a wide valley. The Ravi flows approximately 130 kilometres before entering Punjab and Pakistan.2

Ecological Consequences of Hydro-electric Power Project

Himachal Pradesh's rivers and catchments are under severe strain. Large-scale development initiatives, in combination with climate change, have a demonstrable impact on natural ecosystems and runoff characteristics. Water resource strategies will need to strike a careful balance between development and economic goals and basic requirements for conservation and environmental protection in vulnerable mountain and river ecosystems. Environmental flow maintenance is necessary in the environmental approval process, although it is rarely monitored or enforced. The assessment of acceptable environmental flow is difficult, and additional research is needed to ensure that rivers maintain a minimal level of ecological balance. Dams and abstractions must be strategically placed to limit their impact. Dams have now blocked the majority of rivers, obstructing fish migration. Future dams, on the other hand, might be properly placed to reduce their impact. The provision of fish passes should be taken into consideration.

Over the previous few decades, there has been an increase in environmental knowledge and concern. This has been related to proposals for better development approaches since the mid-1980s. More recently, there have been increasing efforts to understand the causes of these environmental problems and to address the policy for, and political aspects of, development and environment. Right from the outset, the building of a large-scale dam causes irrevocable environmental destruction. Sadly, this destruction does not end with the filling of the reservoir and the inevitable loss of land, forests and wildlife. In truth, there is scarcely an aspect of the dam’s future operations which will not carry a heavy environmental cost.3

Dams have the potential to cause earthquakes. Over 100 earthquakes have been found around the world that scientists believe were produced by reservoirs.4 It has only recently been recognized that the pressure applied to often fragile geological structures by the mass of water impounded by a big dam can – and often does – give rise to earthquakes.3 The 7.9-magnitude Sichuan earthquake in May 2008, which killed an estimated 80,000 people and was linked to the construction of the Zipingpu Dam, may be the most devastating occurrence. Dr. V. P. Jauhari wrote about this phenomenon, known as Reservoir-Induced Seismicity (RIS), in a paper prepared for the World Commission on Dams: "The most widely accepted theory for how dams cause earthquakes is that the extra water pressure created in micro-cracks and fissures in the ground beneath and near a reservoir causes earthquakes. When the pressure of water in the rocks rises, it works as a lubricant, lubricating faults that are already under tectonic strain but are prevented from slipping by friction between the rock surfaces".5

Environmental loss due to large dams has been described by Ramaswamy R. Iyer6 as under:-

Let us now look at the specifics of major dams' environmental impact. The phrase "environmental impact" is used in the broadest sense possible here. There is a curious view that the displacement of people is not an ‘environmental’ aspect. Whatever we may call it, it is certainly a very important aspect, and it is difficult to see how anyone can object to this issue being raised by the environmentalists. The environmental impact of large projects of this kind would include:

The loss of agricultural and forest land through submergence under the reservoir which is created;

The project's displacement of people and animals, as well as the loss of jobs, causing significant suffering to the landless and indigenous populations;

The displacement of wild animals and the possible extinction of some rare flora and fauna;

The public health issues that may arise as a result of large-scale water impoundment and possible climatic changes;

The inherent hazards of huge dams (the likelihood of breaches and dam-bursts, resulting in the flooding of wide areas), particularly in seismically active places, as well as the problem of reservoir-induced seismicity;

The loss of vegetation in the upper catchment, resulting in excessive run-off and loss of top soil, resulting in faster siltation of the reservoir and a reduction in its useful life (this might be considered an example of the project's environmental impact); and

The onset of water-logging salinity in the project's command area after several years of irrigation, resulting in the abandonment of important agricultural land.

Construction activities in the dam region nearly usually result in a large increase in dust levels in the air. Such dust not only harms the region's woods and other vegetation, but it also pollutes the river and other bodies of water. People who live and work in the region's health are also affected significantly. Construction activities, such as diverting the river through a tunnel, produce enormous disruptions and have negative consequences for the aquatic ecosystem. Vulnerable species with limited distribution or low tolerance often become extinct even before the dam is constructed.7

According to Patrick McCully, Executive Director of the International Rivers Network, few people are aware that the reservoirs behind dams are a major source of global-warming pollution. The huge hydropower business, which has been chastised for polluting rivers and evicting villages that stand in the way of its reservoirs, has taken the opportunity to rebrand itself as climate-friendly. When a large dam is built, the reservoir floods plants and soils that contain massive amounts of carbon. This organic waste rots underwater, releasing carbon dioxide, methane, and, in some cases, nitrous oxide, a highly strong global warming gas. Although emissions are highest in the first few years after the reservoir is built, they can last for decades. Because the river that feeds the reservoir and the plants that grow there will continue to offer additional organic matter to drive greenhouse gas production, this is the case. Some of the emissions make their way to the surface of the reservoir. The rest takes place at the dam. Like the fizz from an opened bottle of soda, methane-rich water shoots out of turbines and spillways, releasing its methane. When these 'fizz' emissions are taken into account, estimates of hydropower's global warming impact increase. Although reservoirs generate greenhouse gases in all temperature zones, these emissions are typically worse than those caused by fossil fuels in the tropics. He goes on to argue that given the large sums of money at stake in carbon-trading programmes and other measures to combat global warming, it's understandable that the hydropower business is concerned about being labelled as another global-warming contributor.8

In addition, it has been reported that, in Himachal Pradesh, hydel projects, in addition to slate mining and industrialization, have been a major source of interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) for the labourer class in recent years. Employees, particularly labourers, have developed silicosis and sarcoilosis as a result of hydel projects and slate mining. According to Dr. S. Kashyap, Principal of Indira Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Shimla, the number of people suffering from these disorders has increased dramatically in the recent few years. He also stated that silicosis tuberculosis was a common and unusual condition among slate-mine workers in Chamba, Dharamsala, and other places. Large hydel projects in Kullu, Kinnaur, Lauhal-Sapiti, Mandi, and other areas of the districts have also exacerbated ailments among the working class.9

In India, the environmental and social consequences of major dams were poorly recognised, and the avoidance and mitigation of negative consequences were frequently overlooked in financial and commercial calculations. This has been stated by Shekhar Singh and Pranab Banerji10. Though things have improved in the recent past, the situation remains far from satisfactory. Judge11 in his paper argues that in the understanding of environmental management, the project-affected people should constitute the first priority. There is a need for taking stock of the nature and needs of human society as well as the logic and character of economic development. He further questions whether society should develop at the cost of destroying the socio-economic and ecological basis of a community, and is development benefiting the privileged and further pauperizing the unprivileged. Hirsch12 said that the age of large dams is drawing to a close. Yet the number and scale of dams that are on the cards is indicative of the destruction that remains to be wrought on vulnerable people and fragile environments if these projects are allowed to go ahead. As a matter of logic, increasing scarcity of suitable sites for dam construction means that each new site tends to be in a more vulnerable area than the last.

Review of Literature

According to Rajeshwari Tandon13, both man-made and natural heritage are areas of concern in terms of heritage — the entire ambience and unique way of life, including the hill areas, must be maintained. There is a need for the State Government or Local Bodies to compile a list, document it, and enact legislation. A strategy on afforestation and soil conservation is also required, as is a policy on encroachments, road widening without causing harm, and a framework for controlled approaches for longer-lasting roads. Another crucial topic is disaster management, particularly in the case of earthquakes. The importance of community involvement cannot be overstated, as no programme can flourish without active community participation.

Tehri Dam, in Uttaranchal State's Garhwal Himalayas, requires the submersion of Tehri town and 23 villages in its vicinity, according to Vijay Paranjpye's14 assessment. A total of 72 communities in the surrounding area have been impacted in some way by this procedure. Around 85,000 people have been displaced as a result of the dam. Local residents have occasionally expressed their displeasure with the dam. They believe the Bhagirathi to be a sacred river, and they are concerned that the project will irrevocably ruin a number of holy sites downstream. People are also aware of the government's poor track record in rehabilitating dam oustees in other parts of the country where large-scale displacement occurred. They also fear that a large dam in the vicinity will break sooner or later due to the area's complicated geological and seismic circumstances, flooding the entire valley and destroying everything they hold dear and precious.

Mathur and Cernea15 contribute a large collection of empirical facts as well as critical analysis to the present settlement debate. Both voluntary and involuntary resettlements have been studied by the authors. This volume is well positioned to expand the policy debate and contribute to improving the practise of resettlement, as the concerns of displacement, resettlement, and rehabilitation have recently been more controversial and contested than at any other time in the past. Scudder16 shows the reader the human side of huge dams, past, present, and future: population resettlement, hydroelectric power benefits, water resource development, flood management, and ecosystem destruction. He finds that the traditional cost-benefit analysis of major dams has been proven to be fatally flawed.

Barrow17 examines the sources and implications of global environmental problems in the past, present, and future, and suggests, where possible, ways in which they might be reduced or avoided through prudent management. Some of these issues are caused by natural factors, while many environmental issues are the result of flawed development ethics.

Thus, it is clear that various problems have been surfacing frequently wherever river dams are being proposed and constructed at different locations all over the world and in India. It is with this in view that we decided to investigate the issue of displacement and resettlement by looking into the experiences of people affected by the construction of the Chamera Dam in Himachal Pradesh.

The Chamera Hydro-electric Power Project

The Chamera Hydro-electric power Project Dam has been constructed by the N.H.P.C. which generates electricity to the tune of 540 Mega Watt. It is a major project for accelerating development of hydropower in Himachal Pradesh. It is constructed as Indo-Canadian Joint venture by N.H.P.C. Actual construction work of the project was commenced in 1985 and the project was commissioned in March, 1994. The completion cost of the project is Rs. 2114.02 crores. The project comprises 140 metres high concrete dam, a 9.5 meters dia and 6.41 kms long Head Race Tunnel, a 25 M dia and 84 M high surge shaft, a 8.5 metres dia and 157 metres high pressure shaft and an underground Power House housing 3 nos Francis Turbines and generating units of 180 MW each.

|

Figure 1: Study Area Click here to view Figure |

Methodology

A survey approach has been selected as a principal means for data collection from the people affected by the construction of Chamera Hydro-electric power project in Chamba. The interview method was adopted for collecting data which was supplemented by on the spot observations and informal discussions. Head of the each family has been interviewed to get the basic information. Survey has been conducted with the help of a well designed interview schedule, which broadly covered aspects such as loss of green cover, loss of access to common property, loss of flora and fauna. The Interview Schedule has been flexible with some open ended questions having been included in it.

Four villages have been selected for the study, viz. Chakloo, Palehi, Thari and Bhanota. Because they are worst sufferers of the Dam. Eighty families have been selected (Twenty families from each village). The technique of systematic Random Sampling has been applied for the survey and 20 per cent of the affected families have been covered from each village. List of affected families was obtained from the office of the Relief and Rehabilitation Officer (RRO) of the Chamera Hydro-electric Power Project. All the respondents of the study are from rural area. The youngest respondent in our study was 25 years of age and the oldest 80 years old. The majority of respondents belong to the age group of 25 to 55 years.

Damage to Environment due to Construction of Chamera Dam

Development policies and programmes have consistently failed to pay careful attention to the issue of environment and adopt approaches that may result in many adverse impacts on the environment and the ecology of the area.

Developmental projects causing mass displacement, not only lead to erosion of cultural diversity, but also, cause the destruction of biological diversity. While ecological imbalance seriously threatens the survival of those dependent on it, the imposition of external technologies on it disrupts the natural genetic diversities that have taken years to evolve. The overall consequence of all this is a degradation that is almost irreversible.18

Loss of Green Cover

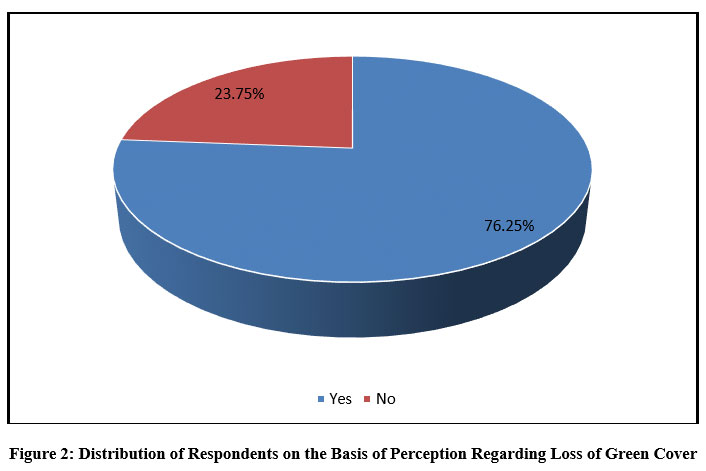

Dams which are normally constructed in the hill areas create large impact on environment of the area, as is the case in the constructon of Chamera Dam Project shown in Figure 2. Out of the total eighty respondents, sixty one (76.25 per cent) complain of the loss of green cover, whereas, nineteen (23.75 per cent) respondents do not feel the loss of green cover.

|

Figure 2: Distribution of Respondents on the Basis of Perception Regarding Loss of Green Cover. |

Loss of Access to Common Property

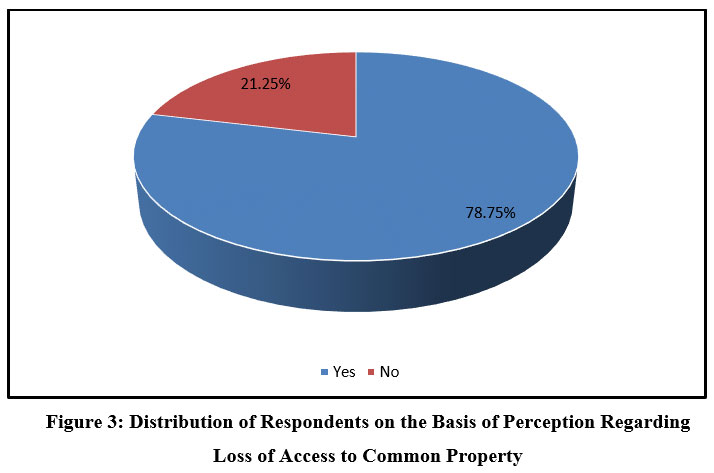

Whether displaced people are resettled within a reservoir basin or elsewhere, a major cost of large dams to the indigenous people is loss of common property resources, such as forests, rivers and grazing lands etc.

|

Figure 3: Distribution of Respondents on the Basis of Perception Regarding |

From Figure 3, we can infer that sixty three (78.75 percent) respondents out of the total of eighty believed that they suffered the loss of access to common property. Seventeen respondents, i.e., 21.25 per cent do not feel any loss to the common property resources. When we came in contact with Pritam Singh, one of the respondents, he told that, “Pahale paani ke chasme the jo doob gaye, paani bada achha tha. Samsan ghat tha jo ab nahin hai. Pashu charane ke jagah nahin rahi, gharat bhi chale gaye. Ab har kaam ke liye door jana padata hai.” (Previously there were water springs which have been submerged. Drinking water was clean and pure. There was crematorium which is not there. There are no grazing fields now or the water mills. Now we have to go far off places for every work). So it is clear that the Chamera Dam has also caused damage to the common property resources as has been emphasised by Cernea.

Loss of Flora and Fauna

There are certain local species of plant and animals that are special to the area which are related closely enough to interbreed naturally. Such species are in danger when any developmental activity starts in the area. Figure 4 shows that twenty one (26.25 percent) respondents were of the view that there is a definite loss of flora and fauna in the area due to the construction of Chamera Dam, whereas a majority of fifty nine (73.75 per cent) did not think so.

|

Figure 4: Distribution of Respondents on the Basis of Perception Regarding |

In the construction of Chamera Project, clearly much loss to the different environmental aspects has incurred. On environmental aspect, our data show that fifty nine (73.75). respondents believed that the area suffered the loss of green cover due to the construction of Chamera Dam. There were as many as twenty one (26.25 percent) respondents who felt the loss of flora and fauna. They said that the area was earlier full of natural orchards which bore local species of fruits. Those are now extinct and their children are unaware of such species of local fruits.

Additionally, sixty three (78.75 percent) respondents complained the loss of access to common property due to the impoundment of water in the reservoir. They are facing great hardships as the reservoir invariably submerged large tracts of forest and eco-systems, including grasslands etc. The people of Chakloo, Palehi, Thari and Bhanota villages told that they are the worst sufferers of the Dam. They have lost access to the common property, especially the natural water-springs. Besides, there were small water-mills (Gharats) on the banks of river where people of the nearby villages used to get various cereals, like wheat and maize, ground to make flour. Now they have to go to far-off distances to get the flour which costs them dearly as they would go in the morning and return in the afternoon after getting the flour ground through mechanical machines, which, they say, burn most of the energetic contents of the cereals. They have also lost natural grazing fields for their cattle. In addition, the local people have lost their traditional crematorium on the banks of the river and now the dead bodies have to be cremated on the fringe of the reservoir and as such the ash and the remains, which were considered sacred to be carried away by the running water of the river, are now seen floating on the surface of the reservoir water.

Another point that emerged when we further delved into the situation that our respondents have been facing due to construction of Chamera Dam, is the submergence of forests. Attempts to compensate for the loss are often made by seeking to reproduce such ecosystems elsewhere. Natural ecosystems, on the other hand, cannot be recreated. A plantation can be created, but not a natural forest or grassland. According to available research, compensatory afforestation is difficult to perform and, in some cases, was not completed until several years after the project was completed. If a specific type of forest is depleted in a given region as a result of the dam, it must be compensated by the creation of another forest in the same location. In many situations, compensatory afforestation is carried out in locations and ecosystems that are vastly different from those for which it was intended.

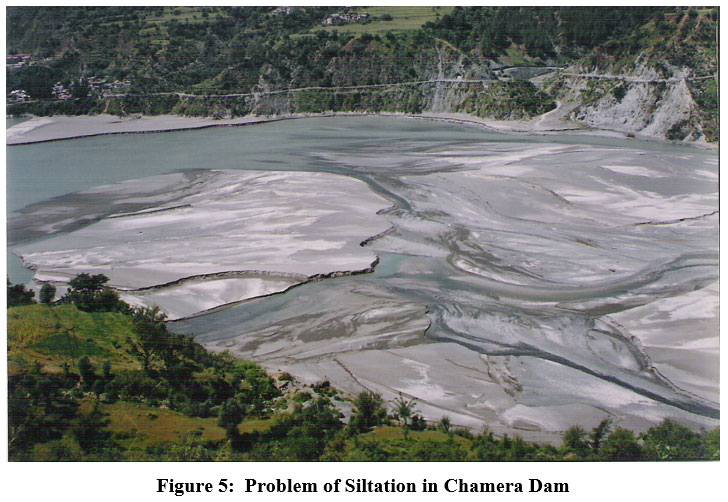

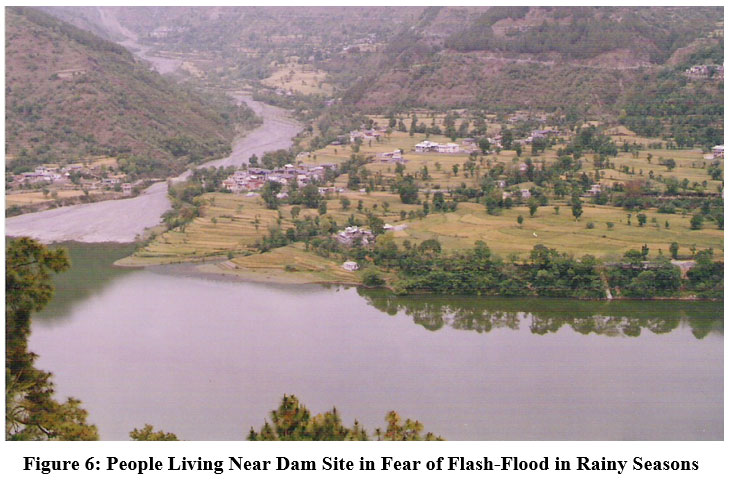

The history of dam construction includes many cases in which the ecological and environmental damage caused by sediment accumulation in reservoirs has been severe and difficult to repair. Sedimentation deposition is the most serious impact of dams which result in a loss of storage capacity of the reservoir due to deposited sediment.19 This has been seen in the Chamera Dam reservoir as well. Sedimentation deposition has extended some distance of the reservoir upstream. This has increased the surface and raised water level in the surrounding villages. In some areas deposits have been exposed during long periods of reservoir drawdown and some times wind-blown dust has become a significant problem. During the field work, some respondents told that in the rainy season when it rains heavily, the water of the rivulets, which form part of the reservoir, recedes and enters their fields and houses. These families live in fear of being washed away by flash floods which may occur during the rainy season.

|

Figure 5: Problem of Siltation in Chamera Dam. |

|

|

|

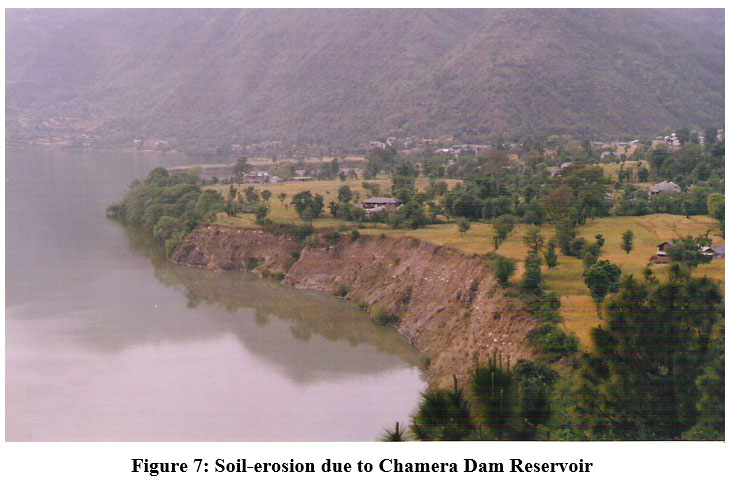

Ficture 7: Soil-erosion due to Chamera Dam Reservoir |

There is also the loss of green cover due to the Dam construction and many rare local species of fruit plants and forests have been lost. People have also lost their grasslands etc. Moreover, there is soil erosion on the edges of Chamera Dam reservoir. It came to our notice that as promised, no land in lieu of land was given to the displaced families and no colonies have been made to resettle the displaced persons. All the respondents told that they lost much of their cultivated land due to the construction of the Project.

Conclusion

Since the construction of the project has been considered as an essential pre- requisite for the development of the area, adverse consequences and environmental degradation have been overlooked by the politicians, planners, policy makers as well as, administrators. It has clearly been forgotten that environmental degradation is not simply the ecology, flora and fauna, but also the quality of human life. Developing countries planned and are planning to establish industries, dams and other developmental projects both in rural and urban areas without taking into consideration the environmental problems associated with the misuse of natural resources like soil, water and forests. They overlook and disregard the fact that there are many intended and unintended consequences of the development processes. For instance, while treating environment as a resource, there is an imminent threat to the natural environment of the developing countries with the rapid industrialization and urbanization. The protection of environment should be considered as a crucial component of development planning. Development will be hampered without effective environmental protection, and without development, resources will be insufficient for much-needed investments in important economic and social areas. Therefore, a strong case for combining the concerns of environment; both must be designed to ensure sustainable development. Hence, there is a need of ‘sustainable development’, which implies a kind of development which can sustain ecology, as well as, conserve and preserve the existing natural resources.

It may be more beneficial, both economically and environmentally, to construct large number of small dams in the catchment areas of rivers. Such projects may cost less and may also prove more beneficial in the long run. Environmentally, small dams and hydro-electric projects may be more suitable in the fragile eco-system of regions like Himalayas. But micro hydro projects should not be allotted in an indiscriminate manner ignoring the traditional rights of the local people and the environment. Keeping in view the fragile hill strata, the Government should be very selective and should not allow more than one project on one stream. If large number of projects are allowed to come up, these streams, which are vital to the local eco-system, will be virtually wiped out. As a result, the people will loose their traditional sources of water which cater to their need for drinking, irrigation, livestock and even running the water mills.20 While ecological imbalance seriously threatens the survival of those dependent on it, the imposition of external technologies on it disrupts the natural genetic diversities that have taken years to evolve. The overall consequence of all this is a degradation that is almost irreversible.

By the time the Government of Himachal Pradesh takes decision to do away with the construction of large projects in the state, it would be too late since much damage to the fragile ecology and environment of the hilly state would already have been done. Large-scale projects earn greater kudos for politicians and engineers alike; the more grandiose the scheme, the more prestige accrues to those involved in its construction. It is reasonable to assume that governments and other developmental agencies pay little attention to the ecological and social problems caused by large dams. So there seems a remote possibility that the Government of Himachal Pradesh at this stage would review the policy of constructing large dams in the state since the work on the construction of many large dams has already been awarded to different sectors and many more are under construction. The fact of the matter is, that there has not been any definite policy of the Government and in the absence of such policy, people were made to suffer due to the ill-planned, badly executed, inadequate and inappropriate rehabilitation programme. There is thus a need to formulate a comprehensive national policy for the construction of various projects in the country with environmental, economic and socio-cultural impact assessment through national legislation.

Keeping in view the above points, some suggestions are offered. As the mega hydel projects result in submergence of large tracts of fertile lands, displace villages falling under the catchment area, involve huge expenditure as difficult terrains to be negotiated, the state of Himachal Pradesh should now concentrate on the mini-and-micro hydel projects. It may be more beneficial, both economically and environmentally.

Acknowledgment

I am also thankful to the respondents for helping me in providing the data that forms the basis of this study.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

The author have received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- State of the Environment Report, Himachal Pradesh, 2000.

- Asian Development Bank (2010) “Climate Change Adaptation in Himachal Pradesh: Sustainable Strategies for Water Resources”.

- Goldsmith, Edward and Nicholas Hidyard (1984) The Social and Environmental effects of Large Dams. Camelford: Wedebridge Ecological Centre.

- Gupta, Harsh. K., Earth-Science Reviews. Volume 58, Issues 3-4, October 2002, Pages 279-310.

CrossRef - Jauhari, V. P., (1999) Prepared for Thematic Review IV.5. “Options Assessment-Large Dams in India-Operation, Monitoring and Decommissioning of Dam” .

- Iyer, Ramaswamy R. (2003) Water: Perspectives, Issues, Concerns. New Delhi: Sage.

CrossRef - Singh, Shekhar and Pranab Banerji (eds.) (2002) Large Dams in India. New Delhi, Indian Institute of Public Administration.

- McCully, Patrick (2006) “Not so friendly: hydropower adding to climate change”, The Tribune. Chandigarh: December 28.

- Kashyap, S. (2006) “Hydel projects causing interstitial lung diseases”, Chandigarh: The Tribune, October 9.

- Singh, Shekhar and Pranab Banerji (eds.) (2002) Large Dams in India. New Delhi, Indian Institute of Public Administration.

- Judge, Paramjit S. (2000) “Resettlement and Rehabilitation of the Displaced” in S. N. Chary and Vinod Vyasulu (eds.) Environmental Management; an India Perspective. Delhi: Macmillan.

- Hirsch, P (1987) Dammed or Damned? In People and Dams. New Delhi: Society for Participatory Research in Asia.

- Tandon, Rajeshwari and Sarah Quraishi Alam (eds.) (2003) A case for conservation of heritage and environment of hill stations and hill areas. New Delhi: INTACH.

- Paranjpye, Vijay (1988) Evaluating the Tehri Dam: An Extended Cost Benefit Appraisal. New Delhi: INTACH.

- Mathur, Hari Mohan and M. Cernea (eds.) (1995) Development, Displacement and Resettlement. New Delhi: Vikas.

- Scudder, Thayer (2005) The Future of Large Dams. London: Earthscan.

- Barrow, C. J. (1995) Developing the Environment. Harlow: Longmans.

- Kothari, Rajni. (1984) “The Non-Party Political Process” Economic and Political Weekly, February.

- ICOLD, Committee on Public Relations (1997) Benefits and Concerns about Dams.

- The Tribune (2007) Environment, the first casuality. Chandigarh: March 9.