Sustainable Community Forestry: Insights from Rural Thailand

Corresponding author Email: s.rout@uohyd.ac.in

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.16.3.8

Copy the following to cite this article:

Rout S. Sustainable Community Forestry: Insights from Rural Thailand. Curr World Environ 2021;16(3). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.16.3.8

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Rout S. Sustainable Community Forestry: Insights from Rural Thailand. Curr World Environ 2021;16(3). Available From:

Download article (pdf)

Citation Manager

Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 03-07-2021 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 11-12-2021 |

| Reviewed by: |

Jaipal Sharma

Jaipal Sharma

|

| Second Review by: |

Okon-akan

Okon-akan

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Hemant Kumar |

Introduction

In developing societies of South and South-east Asia, forests have been the sites of contestation and social conflict to define, negotiate and reconstruct the meaning and practice of democracy, social justice and citizenship.1 The social history of forest management in Thailand mirrors a similar kind of conflict in the woods between the forest dependent upland minority ethnic groups and the aristocracy of Siam, replaced by the modern Thailand government in the later years. On the one side of the conflict, there have been professional foresters who always believed increased timber production - the sole motive of scientific forestry - can be possible only through exclusion of humans from the forests; and on the other side, there have been peasants, pastoralists and indigenous communities for whom access to forests has been crucial to economic survival. In the midst of such conflicts over forest and the modern Thailand’s attempt to establish state control over the country’s vast natural resources, Thailand has witnessed community participation in forest management practices since 1980s. Over the last few decades, there has been a paradigm shift in community’s role in forest management practices in Thailand. Community forest management, albeit not being a formal system, has evolved in Thailand as a de-facto practice, and has represented an important aspect of Thai culture.2, 3 As per the available evidence, more than 8300 communities have registered themselves with the forest department Government of Thailand to carry out community forest management in the country.4

Situated in this broader context of community-based natural resource governance, this article examines the evolution and current practice of community forest management in Thailand from a socio-historical perspective. To be specific, the article examines the social history of forest governance practices in Thailand and explores the community’s response towards deforestation, resource degradation and rising livelihood insecurity. The article answers specific research questions as to what has been the social-history of forest governance in Thailand, and how the community participation has been institutionalised into forest governance practices in recent times. Besides the secondary sources of data, the article draws insights from three case studies of successful community forestry sites in rural Thailand.

Chronological Overview and Evolution of Forestry Transformation in Thailand

We may identify three succeeding phases of social history of Thai forest as it evolved from the late 19th century onwards. We begin with the influence of early European colonial rule in the neighbouring countries on Thai forestry, and then move on to the American influence of the 1960s, and finally, the recent community uprisings demanding a niche for itself in forest governance in Thailand. Based on their focus on nature, we term these three phases as (a) extracting the nature, (b) conserving the nature, and (c) governing the nature.

Extracting the Nature: The British Colonial Impact on Thai Forestry (late 19th Century – mid 20th Century)

Albeit a history sans colonisation, the colonial forestry of the neighbouring territories has had a profound influence on forest management in Thailand. During the Sukothai (1238 – 1350) and Ayutthaya (1350 – 1767) Period, all land in Thailand was regarded as the property of the monarchy. Yet, local traditions and customary laws ensured the right to access to land for agriculture and other purposes. The change began from the Rattanakosin Period (1782 onwards) when the colonial powers started extracting timber from the neighbouring countries. When the British colonial logging industry expanded from Mon territory to neighbouring areas of Thailand, timber producing trees teak became commercially lucrative, leading to severe competition among the Burmese and the Mon teak treaders.5 The intense competition for logging and case of bribery to northern Lanna Lords to gain such concessions resulted in overlapping concessions being provided to the timber traders.6 To gain control over this chaotic condition, the Bangkok Monarchy implemented legislations in 1874 and 1883, after which any contracts between foreigners and the northern lords required Thailand’s central government’s approval.7

By the end of the 19th century, the teak forests of North and North-western Thailand had proved to be economically valuable, and therefore, politically significant and sensitive. The temporary closure of the Burmese forests during the period to timber cutting caused the British logging companies to expand their operation across the border up to Siam – the present day Thailand.8 The realisation of the economic value of the forest resources, the chaotic conditions created in the area due to constant disputes over logging concessions, and the threats of intrusion into the northern territory by the British colonial power prompted the Bangkok monarchy to take more effective control over forests. Towards the end of 19th Century, the Forest Department was formed in Thailand (in 1896) under the leadership of the British forester Herbert Slade, who served as former Deputy Conservator of Forests in Burma. In the following years, the RFD set up the forest bureaucracy in Thailand, modelled on the Burmese system, and introduced several legislations similar to that of British colonial forestry in South and Southeast Asia.9

With the establishment of the RFD, an organised attempt to establish state control over the forest through scientific forestry emerged in modern Thailand, which also witnessed the end of northern lords’ control over forests. The scientific forestry, based upon the German model and already in practice by the time in the colonial neighbours, tried to transform the natural forests of Thailand into an administrative forest with certain preferred species having a market value. In the initial decades of the 20th century, two relevant laws were passes, i.e. Forest Maintenance Act, 1913 and Forest Management Procedures Act, 1913, which consolidated the state authority to control logging and other forest products. In 1938, the Protection and Preservation of Forests Act was passed with an objective “to nurture sustainably the forests which are national property, and for national interest, there must be methods to control, protect and separate the land from that to be cleared by the people”.10 The 1938 Act defined forests as ‘public treasury of wild and unoccupied land’, where the public treasury included all types of public assets being used for public goods. Further, the Forests Act, 1941 stated that ‘forest means the land which is not yet occupied by anyone according to the Land Act’.

The prime objective of forest management practices in Thailand during this phase was revenue generation from the forests through sustained yield of timber and harvesting other forest produces. Even though Thailand gained from revenue generation through taxation, the power over timber, especially teak concessions, remained with the British colonial timber companies for a long time.5 This gave a boost to the logging companies of Thailand and extraction of timber continued with state patronage.

The scientific forestry and consolidation of state control over forest land in Thailand has had a significant impact upon the livelihood of the forest-dependent communities and consequentially led to sever resistance to the colonial strategies of forest management. Throughout this phase, the relationship between the RFD and the local communities centred on regulation and labour required for carrying out the activities of forest extraction. The forest bureaucracy of Thailand contined to serve the commercial interests of British Colonial power on the one hand and Bangkok administration on the other.8 The worst sufferers of the forest management practices have been those highland communities, who resided in and around the forest, and depended upon the forest for their sustenance. Before the establishment of the RFD and introduction of scientific forestry, while the teak and other large timber were considered as the property of the northern lords, the local communities had access to small trees and other non-wood products. However, with the introduction of the new legislation, the communities found their access restricted to the forest. Ann Danaiya Usher, the Thai environmental historian, therefore, mentions, “the forestry legislation enacted by the RFD criminalised common people’s use of teak by making it illegal to cut teak smaller than 2.1 meters girth, and requiring official permits for logging teak larger than that size”.8

The local response to such restrictions of rights to access to the forest has resulted in uprisings against the state mechanisms, which became much explicit during the last decades of the 19th century. The Phraya Phap Rebellion of 1889 – 90 and Phrae Rebellion of 1901, reflected the forest-dependent community’s resistance to the laws of forest control, and more specifically to the expansion of Bangkok’s political power. Thai historian Chaiyan Rajchagool describes these rebellions as a response to the imposition of new tax regimes from Bangkok, and a reaction against the increasing extraction of teak from Thai forests.11

Conserving the Nature: The American influence on Thai Forestry (the 1950s – late 1970s)

The American wilderness and conservationist thinking had a discernible impact on Thai forestry from the mid-20th century onwards. The forest management practices adopted since the 1950s were more a product of the global political-economy, rather than activities limited to forestry itself. America’s quintessential attempt to dominate the world politics, in an otherwise global context of the cold war and rising communist blocks, through its international aid for economic development, influenced the politics of Thailand as well as forest management practices. The US assistance to Thailand included transfer of technical knowledge on establishment of national parks and forest reserves. The influence of American conservationist thinking on Thai forestry began in the year 1948, when the forest expert group from Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) headed by G. N Danhof visited Thailand to assist the RFD in its efforts of forest conservation. Characterising the hitherto forest management practice as unprofessional, this expert group recommended for conserving two-fifth of the total geographical area under forest cover. During the periods of Cold War, under the aegis of US-Thailand cooperation programme, the American government sponsored visits of bureaucrats, academicians and policymakers from Thailand to the Tennessee Valley and Yellowstone National Park to learn about America’s hydroelectric dam technology and nature conservation systems. Consequently, the American model of development and conservation became ideal for the modern Thai state to imitate.5

The ideas of nature conservation along with economic assistance from the US coincided with the attempt to modernise Thailand under the leadership of the then Prime Minister Field Marshall Sarit Thanarat during early 1960s. Consequently, nature conservation not only became a national symbol par with the monarchy and Thai identity, but also symbolised Thailand’s journey towards modernity.12

From 1960s onwards, Thailand’s forest management policies have been influenced to a great extent by the efforts of conservationists like Dr. Boonsong Lekhakul and George Ruhle. In 1958, Dr. Lekhakul, a medical doctor turned conservationist, published Ha pa mai yang yu yang yuen yong (If the Forest is to Last Forever), which contained a critique of forest management practices of Thailand along with his proposals for reforming Thai forestry in the line of nature conservation.8 Mr. George Ruhle was an American foresters from the US National Park Services, who visited Thailand in 1959 on behalf of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to provide technical assistance to the RFD for identification of forest land to be demarcated as Protected Areas and National Parks. Ruhle travelled extensively in the forests of Thailand and recommended for protection of forests through the establishment of national parks and protected areas in the models of the United States of America. Following this, several forest related legislations were adopted in Thailand, such as the Wildlife Conservation Act, 1960; the National Parks Act, 1961; the National Forest Reserves Act, 1964; which laid the foundation of forest conservation in Thailand. These legislations paved the way for creation of two main categories of protected areas in Thailand: the wildlife sanctuaries, where human presence was restricted mainly to scientific research; and the national parks, where tourism in designated areas was allowed. Two new divisions, i.e. the Wildlife Conservation Division and National Park Division, were created within the RFD to manage these newly created conservation areas. As a follow up to these legislations, the first National Park was established in Khao Yai in northern Thailand in 1961 and the Salak Phra wildlife sanctuary in Kanchanaburi in 1965.

Since then, forest conservation through financial and technical support of international organisations like IUCN, FAO, WWF, USAID, has represented the main face of forest management in Thailand. Starting with the first national park in 1961, Thailand had 16 national parks by 1979 covering an area of 935,700 hectares, which has increased to 114 national parks covering 6.35 million hectares of forests by 2004.13 As per one recent document, there are in total 421 protected areas in Thailand, covering 10,271,900 ha, or nearly one-fifth of the geographical area of Thailand.14

One of the striking features of Thai forestry of this period was that despite Thailand’s multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic character, a monolithic Thai identity dominated the treatment of forests. It was made evident that forests need to be preserved for the ‘national interest’, which implicitly or explicitly meant the interests of the urban, educated Thai population. The forest governance practices of this period, therefore, associated modernity and the dominant Thai national identity with the conservation of forests, undermining the needs and interests of forest-dependent ethnic minorities and indigenous communities. Such a practice of forest governance ignored the pre-existing connection between local livelihoods and the forests. It legitimised the dominance of an ideology which disqualified and excluded the forest-dwelling communities from having a say on forest management practices.

Governing the Nature: Forest Degradation, Emerging Social Conflicts and Community Participation in Forest Management (1980s onwards)

Thailand’s efforts towards nature conservation and the national park and forest reserve discourse ironically coexisted with large scale deforestation. The Royal Forest Department of Thailand conducted the forest assessment survey in 1961, which reported more than half of the area of Thailand (273,628.50 sq. km, 53.33 %) under forest cover.15 Data released by RFD in subsequent years revealed that deforestation has continued in Thailand since 1960s at a sustained rate, albeit adoption of conservation measures. Figure 1 depicts the area under forest cover in Thailand over the last five and a half decades (1961 – 2017). It is evident from Figure 1 that within a period of four decades, there has been a drastic reduction in forest cover in Thailand (from 52.32 per cent in 1961 to 25.28 per cent in 1998). Deforestation in Thailand continued very rapidly between 1961 and 1988, and relatively moderately from 1989 to 1998. Forest cover in Thailand increased from 25.28 per cent in 1998 to 33.15 per cent in 2000; after which it has stabilised to nearly one-third (31 % to 33 %) of the geographical area of Thailand. Despite marginal growth in forest cover since 2000, deforestation has been perceived as a constant problem in Thai forestry.16

|

Figure 1: Changes in Forest Cover in Thailand, 1961 – 2017. Click here to view Figure |

Owing to continued deforestation, forests, which once occupied half of the total land, were reduced to 30 per cent by 1980. Deforestation and degradation of forest land impacted the local communities, who depended on these resources for their livelihood. Consequently, social conflicts over forests erupted in Thailand, forcing the Thai government to completely halt any kind of commercial logging in the forests in 1989.19, 20 The agitation of the upland, forest-dependent, ethnic communities, which brought a watershed in Thai forestry by forcing the government to ban logging concessions in the year 1989, had its origin in the previous decade. The first conflict occurred in the year 1972 when the villagers of Thoen district of Lampang province campaigned against logging concessions, which was quickly followed by similar such protests against commercial logging in other villages.21 By mid-1980s, the movement of the local communities against commercial logging got support from civil society organisations, student and academic communities.22

Albeit the prolonged conflict, in the year 1988, a natural catastrophe visited the Southern part of the country, which created public awareness about the environmental impacts of logging and deforestation. In November 1988, an unusually massive rainstorm in the Southern part of Thailand induced a wave of flash flood and landslide, destroying villages and causing many casualties. Extensive media coverage and involvement of environmental groups publicised the linkages between deforestation and such natural calamities. It strengthened the already visible movement against commercial logging, as a result of which, Ministry of Agriculture came out with a declaration in January 1989 to completely ban the commercial logging in Thailand.23

Community’s involvement in forestry activities in Thailand became stronger after successfully pressing the government to completely prohibit the commercial logging in the forests. The networks of civil society organisations and rural communities, that had played a significant role in the movement against commercial logging, shifted their attention to forest regeneration and demanded a greater role for communities in forest management. Addressing the demands of networks of social movement organisations and responding to the global paradigm shift in forest governance, the RFD drafted the first Community Forestry Bill in 1991. However, the RFD’s draft bill was countered by the civil society networks for extending limited rights to local communities in forest protection. Subsequently, the network of civil society organisations prepared a people’s version of the Community Forestry Bill, which assigned greater rights to the rural communities in use and management of forests. However, the efforts of enacting the Community Forestry legislation got a setback with the military coup in 1991.24

Further, in 1996, a fresh draft of Community Forestry Bill was drafted by the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB) of Thailand and subsequently was approved by the Cabinet. The National Assembly of Thailand (the Parliament) debated over several different version of the Bill in July 2000, and the Lower House of the Thai Parliament passed the Community Forestry Bill in October 2001.25 The 2001 version of the Bill allowed community’s engagement in forest management even in Protected Forests and National Parks. However, in March 2002, the Senate made several revisions to the Bill, curtailing the rights of the local communities and restricting community’s engagement in any forestry activities in the Protected Areas.26 After three decades of struggle and several attempts of institutionalisation of community forestry, finally, the National Legislative Assembly (NLA) in Thailand approved the Community Forestry Bill on 17th February 2019, putting an end to the longstanding campaign of having a voice in forest management by indigenous local communities.27

Theoretical Perspective on Community Forestry

The theortical literature on community forest governance focuses on common property nature of forests and the conditions that could give rise to sustainable governance of these resources. In common pool resources like forests, it is difficult to exclude other potential co-users of the resource and such join use by multiple users leads to subtraction of the resource. Forests, as common pool resources, exhibit two important features, i.e. ‘non-excludability’ and ‘subtractability’. Protection of forests, therefore, requires strong institutional designs to exclude the ‘free-riders’ 28 and evolve property rights arrangements to ensure equitable sharing of the resource among resource users.29,30

Governance of common pool resources like forests needs to overcome two significant challenges, i.e. ‘problem of provision’ and ‘problem of appropriation’. 31 The provision problem pertains to maintaining a sustaibale flow of resources by reducing the free-riding problem, while the appropriation problem is related to equitable sharing of the scarce resource, thereby avoiding conflict among the resource users. Albeit the problems of governing the commons, recent literature has highlighted the role of local communities in successful governane of these resources in an equitable, efficient and sustainable manner. 32 The most important factor for sustaibale governance of forest resources by the local communities pertains to presence of robust institutional arrangements, since these institutions play a crucial role in solving provision and appropriation problems. 33 An an organised and well-defined system of resource governance, institutions have been defined as ‘humanly devised systems that structure the interaction of its members in social, economic and political arenas’. 34 In resource governance situations, institutions constraint some behaviour, while facilitating others. They enforce sanctions negatively when rules of resource user are violated, and positively when such rules are complied. According to Elior Ostrom, what is important about institutions is the prescriptive nature of their rules, which define actions that are required, permited or prohibited in access, use and governance of resources. 31 In recent decades, several research studies have reiterated the significance of institutions in sustainable governance of common pool resources. These scholarly works have highlighted the specific role of the institution in establishing property rights arrangements, strengthening governance regimes and distinguishing commons from open access resouces.35

Literature Review

Since 1990s, there has been a proliferation of literature highlighting collective action by local communities to manage their immediate common pool resources successfully. 29, 30, 36 Offering an alternative system of resource governance, which relies on local communities, these studies have challenged the notion that state control and privatisation are necessarily the only preferred solutions to resource management. Consequently, community management of common pool resources has been acknowledged as a third solution to commons’ problems by scholars ranging from various disciplines. Scholars have attempted to generalise the conditions required for successful resource governance at the community level for local resource management, which Elinor Ostrom termed as ‘design principles’.29

Most of the literatures on community based resources governance engage themselves with the factors responsible for the emergence of community action for resource governance. Scolars identify four categories of factors that play a crucial role in the emergence of local institutions for successful governance of commons: characteristics of the resource, characteristics of the users of commons, particular institutional arrangements for resource management, and the nature of relationship between users groups and external forces and authorities. 29, 32, 37, 38 In terms of resource characteristics, it is mentioned that a relatively higher degree of dependence on the resource and a perceived risk of resource scarcity generate conditions for evolution of local level protection. 39, 40 There seems to be little agreement over impeccable community characteristics for successful governance of common. While many scholars point towards small size and homogenous nature of the group as essential conditions; 41, 42 some others highlight the potential of collective action in heterogeneous social condition. 43, 44 Yet, the evolution of institutions has undisputably been acknowledged as the most important factor in influencing the success of commons governance, owing to the critical functions it fulfils, such as solving the provision and appropriation problems, and check on free-riding.

Over the years, there has been a paradigm shift in global policy and practice concerning forest management, assigning greater rights and responsibilities to local communities in protection and management of forest resources. 32, 45, 46 Recent literature indicates the prevalence of community forestry in significant numbers in Central and Northern Thailand.47, 48, 49 Literature on community based forest governance in Thailand highlight the role of rural community institutions, the intrinsic community – forest relationship, dependence upon forest resources for livelihoods as factors responsible for success of community forestry. As Thai anthropologist Annan Ganjanapan (2000: 188) mentions “... forests not only provides material benefit to forest communities, but also cultural meaning in terms of power and moral ideologies, which underlie their relationship.” 2 The available evidences suggest that in Thailand, community forests are home to more than half million households, who are heavily dependent upon various forest produces for their subsistence and livelihood. 3, 50

Methodology

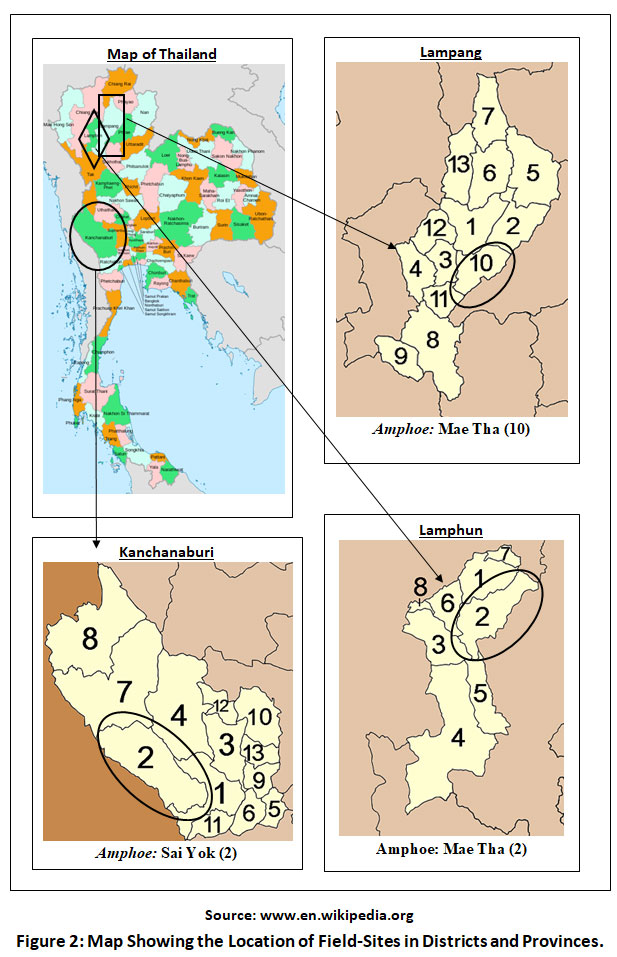

In order to investigate the practice of community forestry in Thailand, the present study adopted case study method for collection of relevant qualitative primary data from the field. We identified three communities in northern and central Thailand, who were engaged in management of their local forest resources and contributed significantly towards forest protection. These three communities included the Ban Wan Sing village in Kanchanaburi province in central Thailand, the Ban Sam Kha village in Lampang province and the Ban Tha Pa Pao in Lamphun province in North Thailand (see Maps in Figure 2). Case study, Focused Group Discussions (FGD), and qualitative interviews with local Forest Protection Committee (FPC) were used as relevant methods collect primary data from the field. A local interpreter was hired to translate the interviews from Thai to English. Besides primary research, relevant data on the history of forest governance practices in Thailand were gathered from several secondary published and unpublished sources.

Results

Having discussed the forest governance practices of Thailand and the evolution of community forestry from a socio-historical perspective, this section unfolds the three case studies, which form the core material for the present research. These three cases of community forestry are chosen from three different locations in Thailand. Yet, they hold one thing in common, i.e. the local community’s commitment to institutionalise sustainable community forestry at the grassroots. These three cases unfold the process of community’s engagement in ensuring sustainable forestry as well as sustainable livelihoods.

Community Forestry in Thailand: Unfolding the Case Studies

Case Study 1: Ban Wan Sing Community Forest, Kanchanaburi

The Ban Wan Sing village is situated in the Sai Yok district (Amphoe) of the Kanchanaburi province of Thailand. Agriculture is the main source of livelihood for residents of this village, with a significant dependence on forests. Members of the village community depended upon the forest for food, small timber for house building materials and for supporting agricultural activities. Community forestry started in Ban Wan Singh in the year 1996 as a response to a socio-ecological crisis that emerged due to gradual degradation of forests and the resultant livelihood insecurities. Before the protection activities began, the forest was in a condition of degradation with a lot of logging activities having taken place before the logging ban period. In such condition of degradation, the leaders of the village initiated the idea of forest protection and created awareness among people the benefits of protecting the forests. In the beginning, people were not ready to join the protection committee, and restrict themselves from cutting trees from the forest. The successful examples of community forestry in the Northern part of the country were frequently used to motivate villagers to join the protection activities. Gradually people joined the movement and became member of the village Forest Protection Committee (FPC). The committee has evolved several rules for protection activities and continuously engaged in monitoring those rules to ensure compliance of those rules by the community members. The community has established a strict system of vigil to monitor the destruction of forest by outsiders and non-members of the community.

Case Study 2: Ban Sam Kha Community Forest, Lampang

The Ban Sam Kha village is situated in the Mae Tha district (Amphoe) of Lampang province of Thailand. The village is situated at a distance of 27 kilometres from Lampang, in the Northern part of Thailand. Ban Sam Kha is surrounded by dense forest, and people depended on forest heavily for food, house building material, agricultural support systems and also for gathering forest products to sell in the market. During the latter part of the 1990s, the village faced with the problem of water scarcity. Upon their discussions with several NGO activists and academicians, the villagers came out with the idea of building check dams in the upland hills of the village and protecting the village forests to solve the water shortage. In the year 2002, the Forest Protection Committee (FPC) evolved in the village with the active leadership of the village primary school teacher, and the committee went ahead in successfully building more than 6000 small check dams in the hilly and inside the forests.

Case Study 3: Ban Tha Pa Pao Community Forest, Lamphun

The village Ban Tha Pa Pao is located in the Mae Tha district (Amphoe) of Lamphun province of Thailand. Ban Tha Pa Pao is an agrarian village, with most of its farmers cultivating paddy. Community participation in forest protection began in Ban Tha Pa Pao as a response to forest degradation and subsequent livelihood insecurity. Before the logging ban period, forest areas were heavily degraded due to logging activities. Local people also were engaged in cutting down trees for commercial gain. In such a context of forest degradation, the idea of protecting the forests collectively evolved in the village. The local school teacher called for a meeting of the village leaders and temple priests to discuss the possibility of preserving the village forests. In the year 1994, the FPC was formed in the village, which undertook a large scale afforestation activity in the degraded areas. The afforestation activities caught the attention of the RFD, which rewarded FPC in the year 2000. Over the years, the committee has successfully enacted several rules to ensure forest protection and has evolved a robust monitoring system to ensure rule confirmation by the community members.

The locations of the field-sites indicating their position in the map of Thailand are depicted in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2: Map Showing the Location of Field-Sites in Districts and Provinces. Click here to view Figure |

Forest Dependence, Livelihood and Sustainable Community Forestry

All the three sites identified for the study were situated in the vicinity of the forest area, with a distance of one to three kilometres. In all the three villages, people’s life and livelihood were closely associated with forest, and dependency on the forest was a universal phenomenon irrespective of household’s economic conditions. Variations in economic conditions just created a difference in degree and nature of dependence, rather than eliminating dependence. While landed, rich, farming households looked upon to forest to support their agricultural activities and other household requirements, the poor households depended much upon the forest for their subsistence needs. Based upon our discussions with the community members and the members of the executive committee of forest protection committee, we identified the following significant dependencies upon forest:

Small Timber for Construction

Since most of the houses were built in wooden structures in these villages, dependence upon forest was common for construction material. Besides, communities also required timber for shared facilities, such as temple, common meeting room, village clubhouse and also sometimes for common village festivals and religious rituals. Further, people also collected timber for construction of temporary bridges during rainy seasons over springs or water streams. Such dependency upon the forest, however, was purely need-based, and households collected timber when they were to construct a new house, mostly after marriage to set up a new family.

Dependence on the Forest for Food, Fodder and Fuel-Wood

Dependence on the forest for food, fodder and fuel-wood was a regular activity for the majority of the households in the villages, who depended upon the forest for these three purposes, directly or indirectly. People collected many edible items every day from the forest, such as mushrooms, leaves, roots, flowers, fruits, tubes, bamboo shoots, etc. For some of the households, these items constitute the primary source of food along with rice. While most people used these edible produces for self-consumption, some households also sold them in the market to earn a living. Besides, people also collect several dry fruits, barks, dry flowers and roots to be used as spices in cooking.

Community’s Dependence upon Forest

Socio-Cultural Dependence

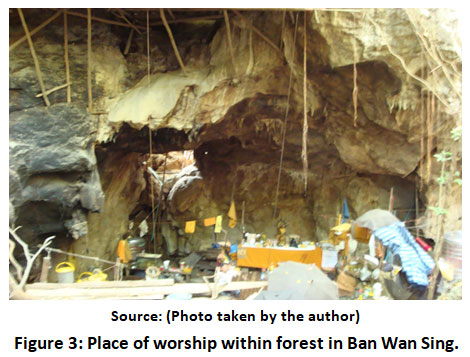

Besides meeting the day-to-day livelihood requirements from the forest, people shared close cultural and spiritual ties with the forest. In the village Ban Wan Sing, the village burial ground existed inside the forest, and people believed that spirit of the departed members lived inside the forest. People used to offer praying in these locations of the forest to satisfy the spirits of the deceased. Forests for these communities meant a cultural and spiritual symbol, through which they connected themselves with their forefathers. These localities within the forest were usually considered sacred, and people were scared to cut trees from these locations (see Figure 3). Community’s dependence upon the forest, therefore, transcended mere economic gains, and the socio-cultural ties and spiritual beliefs bonded people with their local natural resources.

|

Figure 3: Place of worship within forest in Ban Wan Sing. Click here to view Figure |

Collection of Herbs and Medicinal Plants

The elderly and other prominent personalities of the community were found to possess traditional knowledge about several herbs and plants that have medicinal value. It was reported that people collected several types of grass, barks, roots and flower of certain trees, several kinds of vines, for treating diseases like the common cold, flu, cough, etc. Even it was reported that there are certain plants, products of which are used for severe diseases like malaria, blood pressure, joint pains etc. Community members were found to have sufficient indigenous knowledge about medicinal values of plant varieties existing in the forests.

Institutionalising Sustainable Forest Governance Systems

In all the three villages, community forestry institutions evolved as a response to livelihood insecurity arising out of forest degradation. It was reported that forest areas were sufficiently degraded during the pre-logging ban period by the action of the RFD as well as local villagers, who were rampantly engaged in deforestation for commercial gain and for annexing forests to agricultural land. The emerging livelihood uncertainty owing to degradation of forests created sufficient reasons for the community members to evolve institutions of forest protection. In their efforts to institutionalise a sustainable forest governance system, communities came out with specific rules governing use and access to forest resources. Available theoretical literature also suggests that rules –whether formal or informal – play a significant role in institution-building for community-based resource management.29, 51, 52

As a first step to institutionalise sustainable community forest governance systems, all the three communities set out clear cut rules regarding the boundary of their protected forest. The Forest Protection Committee (FPC) of Ban Wan Singh in Kanchanaburi province put up one exhibition board on the entrance to the forest, indicating the area of forest it has taken up for protection (see Figure 4).

|

Figure 4: Community Forestry Board in Ban Wan Sing. Click here to view Figure |

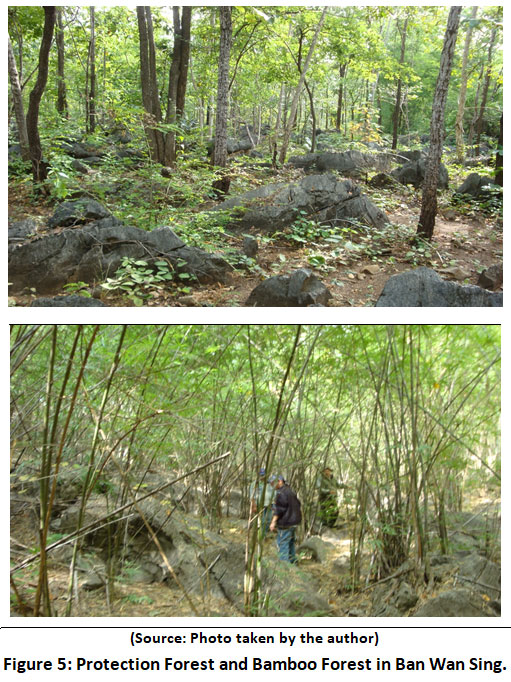

The exhibition board created awareness among local communities regarding the forest protection activities and also served as a notice board to disseminate rules regarding forest use and protection. The Ban Wan Sing FPC bifurcated its boundary between protection forest and bamboo forest, with strict rules of a complete prohibition of tree felling from the former, while allowing some relaxations in the bamboo forest (see Figure 5).

|

Figure 5: Protection Forest and Bamboo Forest in Ban Wan Sing. Click here to view Figure |

The Forest Protection Committee in Ban Sam Kha in Lampang erected stone pillars to distinctively demarcate their area of forest protection. The FPC in Ban Sam Kha divided the forest taken for protection into three Zones (A, B and C) and established different rules of forest use and protection for each Zone. For instance, while it completely prohibited cutting of trees and accessing forest resources from Zone A, several relaxations were granted regarding access and use of forest produces from Zone B and Zone C. It made a rule that the households in need of small timber have to approach the committee for granting permission to do so from Zone B. It earmarked the Zone C – with relatively degraded forest cover - for everyday use of community without any kind of sanctions and permissions (see Figure 6).

|

Figure 6: Zone B (with Rich Forest Cover) and Zone C (relatively Degraded) Forests in Ban Sam Kha. Click here to view Figure |

Likewise, the FPC in Ban Tha Pa Pao in Lamphun Province demarcated its area of protection and divided its protected forest into A, B and C Zones. Forest areas of Zone A existed at the top of the hill, and people were prohibited from accessing and using that part of the forest. Much of the community’s dependence was limited to Zone B forest, from which people appropriated several Non-Timber Forest Produces (NTFPs). Forest in Zone C was used collectively with mutually agreed communal rights, where several households grew mushroom and other forest produces.

Having designed the rules setting the boundaries of protection, the FPCs in all the three communities crafted several other rules for establishing a robust institution for ensuring sustainable forest governance. For example, the Forest Protection Committee in Ban Sam Kha adopted the following mutually agreed upon rules for regulating the access and use of forest resources:

- Entry of any kind of motor vehicles for the purpose of transporting forest produces were prohibited and largescale appropriation of minor forests produces were not allowed.

- Collection and carrying of forests produces such as fuel-wood and small timber were permitted only through headloads or self-carrying.

These rules of forest protection committee put restrictions on choice of technology and instruments used for appropriation of forest products, which in turn governed which type of forest products and in how much quantity can be withdrawn from the forest. Further, rules were framed to provide easy and preferential access to members of the community concerning NTFP collection. The members of the community were allowed to appropriate NTFPs for household use and to sell in the market to earn a living. However, outsiders from the neighbouring villages were permitted to extract a limited quantity of NTFPs, sufficient only for self-consumption. Commercial use of NTFPs and edible forest produces was totally prohibited for outside non-members.

It is essential to point out that while the rules framed by FPCs regulated uncontrolled access and use of forest resources. These rules determined who could access the forest, which part of the forest can be accessed as well as how to appropriate forest resources. While framing these rules initiated community forest governance systems in these three villages, the major challenge for them was to ensure continuity of compliance to these rules, and thereby work towards sustainability principles. For these purposes, the FPC framed another set of rules, which established graduated sanctions for violating any of the other rules. In other words, the FPCs in these three villages evolved a monitoring system, which created an incentive structure of forest access and uses that positively rewarded confirmation of the rules and imposed sanctions when they were violated. For instance, there were rules in place in these communities to impose fines against any kind of violation of protection rules. The sanctions against rule-breaking ranged from simply warning the offenders to initiating legal action with the help of RFD authorities. The committee also imposed fines on habitual offenders, who continued degrading forests despite warning from the committee. The socio-cultural practices and religious beliefs of the communities also helped in evolving an incentive structure, which discouraged people from degrading the forests. Communities used social ostracism and social labelling as effective strategies to ensure compliance of protection rules. Besides, the Buddhist monks preached about forest protection and attempted to connect people with nature through religious practices. The local primary school too emphasised issues of forest degradation. It taught the virtues of forest protection to the young pupils, who in turn, helped in spreading the message of forest protection to the larger society.

Discussion

By adopting qualitative research methods, this paper explored the narratives of sustainable community forestry from three village communities in Thailand. The findings of the study help us to draw certain generalisations about community forestry, especially its potentials to contribute towards establishing sustainable forest governance regimes in Thailand. Community forestry in Thailand holds a good prospect for sustaining the livelihood of the communities as well as the physical conditions of the forest, while at the same time facing certain problems as an alternative system of forest governance. The significant prospects of community forestry emerge from the very nexus between people and the forests. The success of community forestry makes one thing clear that communities – especially those living near forests – have a more significant dependence on forests, and any strategy of forest governance without taking into account this dependence is bound to fail. Similar findings in the context of community based natural resource management have been reported from other locations too.46,53

We identified two specific points that created a rationale for the emergence of community forestry as a sustainable alternative to conventional state-controlled forestry.

First, communities in Thailand, and elsewhere in South and south-east Asia, share an intrinsic, symbiotic and reciprocal relationship with the forest – a relationship that is constantly negotiated and mediated through cultural, ethical and socio-economic parlances. Unlike the state, the communities did not regard forest just as a source of economic benefit, but a complex whole, which provides sustenance in many ways: cultural, social, economic, and political. To agree with noted anthropologist Anan Ganjanapan, “... forests provide not only material benefit to forest communities, but also cultural meaning in terms of power and moral ideologies, which underlie their relationship with nature”.2 It is, therefore, essential to understand the meaning-making process, through which communities assign values towards the forest and connect with nature.

Contrary to the mainstream economic perception, community’s cultural perceptions considered forest as an arena free of state power, morality, and the bindings of mundane life. People also regarded the forest as a place where the spirits of their forefathers reside. The cultural connotations, which assigned such meanings to forests, also constructed norms to value, respect and preserve these resources. Forest governance strategies, when fail to acknowledge such intrinsic relations, often deliver adverse results and face serious challenges. Similar findings have been confirmed by shoclars like As Arun Agrawal and Clark Gibson.45

The second factor, which emphasises prospects of community forestry, is the sheer economic dependence of communities’ on forests. The available shreds of evidence suggest that in Thailand, there are more than 5000 community forests, providing livelihoods to around 500,000 families, who depend upon forest for various subsistence and livelihood requirement. 3, 50 In the studied villages too, the poor households depended significantly on forest to earn a living by selling the NTFP collected from the forests in the nearby market. Forest produces contributed to a great extent to the household economy of many poor households in all the three villages studied. Such being the economic dependency, the involvement of communities definitely holds great promises for the future sustainability of both the household economy and the physical condition of the forest. Community forestry, therefore, holds greater prospects for sustainable livelihoods and forest governance systems in Thailand and other parts of South and South-east Asia, where community’s dependence on forest over a period of time has resulted in evolving an intrinsic and symbiotic relationship between the two.

Conclusion

Approaches towards forest governance have witnessed a fundamental transformation in the developing world since 1980s, favouring an increased engagement of rural communities in forest governance practices. The twin objectives of achieving environmental sustainability and crafting a democratic space over nature have made the communities as integral part of forest management practices. This article attempted to examine the role of community institutions in sustainable forest governance in rural Thailand through an indepth qualitative analysis of three cases of community forestry in Kanchanaburi, Lampang and Lamphun provinces of Thailand. The study concluded that socio-economic dependence upon forests for livelihood and cultural practices symbolising a close and intrinsic relation with forests paved the way for establishing community forestry in rural Thailand. In all the three sites of community forestry, the village forest governance institution adopted a selective approach, where they preserved specific zones within forest by restricting human intervention into it, while at the same time allowing communities to withdraw forest produces from other zones for their day-to-day requirements. Such selective zoning of the forests acknowledged community’s demand on the forest as well as contributed towards protecting forest cover from degradation. The rules crafted by the institutions minimised conflicts over resource appropriation and ensured equitable sharing of the resource. To conclude, the community forestry instituions in rural Thailand not only ensured cnvironmental sustainability, but also contributed towards democratisation of nature by way of creating inclusive spaces in forest governance pracices.

Acknowledgements

The paper is an outcome of Indo-Thai visiting research fellowship, awarded to the author jointly by Indian Council for Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi and National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), Bangkok. The author would like to thank and acknowledge both the organisations for the grants provided for the empirical research. The author would also like to thank Centre for Bharat Studies, Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia, Mahidol University, Thailand for the support and cooperation provided for carrying out the fieldwork for the research.

Funding Source

The empirical research was funded by Indo Thai Visiting Fellowship Grant, jointly sponsored by the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi and National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), Bangkok.

Conflict of Interests

The author agrees that this research was conducted in the absence of any self-benefits, commercial or financial conflicts and declares absence of conflicting interests with the funders.

References

- Guha R. The Prehistory of community Forestry in India. Environmental History. 2001; 6 (2):231 – 238.

CrossRef - Ganjanapan A. Local Control of Land and Forests: Cultural Dimensions of Resource Management in the Northern Thailand. Chiang Mai: Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development, Chiang Mai University;2000.

- Salam M A, Noguchi T, Pothitan R. Community Forest Management in Thailand: Current Situation and Dynamics in the Context of Sustainable Development. New Forests. 2006; 31: 273 – 291.

CrossRef - RECOFTC. Community Forestry Adaptation Roadmap to 2020 for Thailand. Bangkok: Centre for People and Forests, Regional Community Forestry Training Center for Asia and the Pacific (RECOFTC); 2014.

- Laungaramsri P. The Politics of Nature Conservation in Thailand. In: Rajesh N, ed. After the Logging Ban: Politics of Forest Management in Thailand. Bangkok: Foundation for Ecological Recovery; 2005: 48 – 67.

- Shalardchai R. Pa mai Kap Karn Pattana Chonnabot (Forestry and Rural Development). Bangkok: Public Policy Studies, Social Science Association of Thailand; 1979.

- Royal Forestry Department (RFD). The History and Work of the Royal Forestry Department: 1886 – 1957. Bangkok: Royal Forestry Department, Thailand; 1958.

- Usher A D. Thai Forestry: A Critical History. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books; 2009.

- Pye O. Khor Jor Kor: Forest Politics in Thailand. Bangkok: White Lotus; 2005.

- Kaiyoorawong S. Conserving Thailand’s Forests: Legal Perspectives. In: Rajesh N, ed. After the Logging Ban: Politics of Forest Management in Thailand. Bangkok: Foundation for Ecological Recovery; 2005: 68 – 121.

- Rajchagool C. The Rise and Fall of the Thai Absolute Monarchy: Foundations of the Modern Thai State from Feudalism to Peripheral Capitalism. Bangkok: White Lotus; 1994.

- Lekhakul B. Thiew Pa (Wandering in the Forest) Bangkok: Saksopa Printing; 1992.

- FAO. Thailand Forestry Outlook Study. Working Paper No. APFSOS II/WP/2009/22, Bangkok: Food and Agricultural Organisation Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific; 2009.

- Gloss R, Myron L, Ahmed H. International Outlook for Privately Protected Areas. New York: UNDP; 2019.

- Royal Forestry Department (RFD). Forestry in Thailand. Bangkok: Royal Forestry Department, Thailand; 2009.

- Delang C. The Political Ecology of Deforestation in Thailand. Geography. 2005; 90 (3): 225 – 237.

CrossRef - FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment, 2015. Rome: Food and Agricultural Oorganisation; 2015.

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment, 2020. Rome: Food and Agricultural Oorganisation; 2020.

- Hirsch P, Lohmann L. Contemporary Politics of Environment in Thailand. Asian Survey. 1989; 29 (4): 439 – 451.

CrossRef - Lohmann L. Future of Thai Forest Conservation. Environmental Conservation. 1989; 16 (4): 362 – 364.

CrossRef - Boonchai K. Local People’s Movement after the Logging Ban. In: Rajesh N, ed. After the Logging Ban: Politics of Forest Management in Thailand. Bangkok: Foundation for Ecological Recovery; 2005: 162 – 202.

- Sumalan Y. How Participatory is Thailand’s Forestry Policy? In: Harada K, Nanang M, ed. Policy Trend Report, 2004. Kanagawa, Japan: Institute for Global Environmental Strategies; 2004.

- Rajesh N, [ed]. After the Logging Ban: Politics of Forest Management in Thailand. Bangkok: Foundation for Ecological Recovery; 2005.

- Brenner V, Buergin T, Kessler C, Pye O, Schwarzmeier R, Sprung R D. Thailand’s Community Forestry Bill: U-turn or Roundabout in Forest Policy, Socio-Economics of Forest Use in the Tropics (SEFUT) Working Paper No. 3, Freiburg: Albert-Ludwig Universität; 1999.

- Johnson, C. and Forsyth, T. (2002). In the Eyes of the State: Negotiating a ‘Rights-Based Approach’ to Forest Conservation in Thailand. World Development; 30 (9): 1591 – 1605.

CrossRef - Sato J. Public Land for the People: The Institutional Basis of Community Forestry in Thailand. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 2003; 34 (2): 329 – 346.

CrossRef - Bangkok Post. Community Forest Bill Passes NLA. Bangkok Post, February 17, 2019.

- Hardin G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, 1968; 162: 1243 – 48.

CrossRef - Ostrom E. Governing the Commons: Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

CrossRef - Bromley D. W, Feeny D, McKean M A, Peters P, Gilles J, Oakerson R, Runge C F and Thomson J. [ed]. Making the Commons Work: Theory, Practice and Policy. San Francisco: ICS Press; 1992.

- Ostrom E. 2001 An Institutional Approach to the Study of Self-organisation and Self-governance in CPR Situations. In Sankar U, ed., Environmental Economic. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Baland J M, Platteau J P. Halting Degradation of Natural Resources: Is There a Role for Local Communities? Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

CrossRef - Rout S. Sustaining South-East Asia’s Forests: Community, Institutions and Forest Governance in Thailand. Millennial Asia, 2018; 9 (2): 140 – 161.

CrossRef - North D C. Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspective, 1991; 5 (1): 97 – 112.

CrossRef - Rout S. Collective Action for Sustainable Forestry: Institutional Dynamics in Community Management of Forests in Orissa. Social Change, 2010; 40 (4): 479 – 502.

CrossRef - Berkes F. ed. Common Property Resources: Ecology and Community-based Sustainable Development. Dehra Dun: International Books Distributors; 1991.

- Wade R. Village Republics: Economic Conditions for Collective Action in South India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988.

- Agrawal A. Common Resources and Institutional Sustainability. In Ostrom E, Dietz T, Dolsak N, Stern P C, Stonich S and Weber E U (eds.), The Drama of the Commons. Washington D. C: National Academy Press; 2002.

- Singh K. Managing Common Pool Resources: Principles and Case Studies. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1994.

- Ostrom E. Self-Governance and Forest Resources. Occasional Paper No. 20. Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research; 1999.

CrossRef - Olson M. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1965.

- Esman M J and Uphoff N. Local Organisations: Intermediaries in Rural Development. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press; 1984.

- Vedeld T. Village Politics: Heterogeneity, Leadership and Collective Action. Journal of Development Studies, 2000; 36 (5): 105 – 134.

CrossRef - Varughese G and Ostrom E. The Contested Role of Heterogeneity in Collective Action: Some Evidence from Community Forestry in Nepal. World Development, 2001, 29 (5): 747 – 765.

CrossRef - Agrawal A, Gibson C C. Enchantment and Disenchantment: The Role of Community in Natural Resource Conservation. World Development. 1999; 27 (4): 629 – 49.

CrossRef - Lynch O J, Talbott K. Balancing Acts: Community Based Forest Management and National Law in Asia and the Pacific. Washington D.C.: World Resource Institute; 1995.

- Poffenberger M, ed. Keepers of the Forests: Land Management Alternatives in Southeast Asia. Oakwood: Kumarian Press;1990.

- Ganjanapan A, Ganjanapan S. ed. Research Report on the Cases of Community Forestry in the North. Chiang Mai: Social Research Institute, Chiang Mai University; 1991.

- Galli D. Tragedy in Commons or Mutual Success: Assessment of Community-based Forest Management in Western Thailand. Unpublished Masters Thesis, School of Environment, Resources and Development, Asian Institute of Technology (AIT), Bangkok; 2007.

- Samabuddhi K. Academic Slams Senators over Ban, Bangkok Post, 29 March 2002.

- Ostrom E. Background on the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. Policy Studies Journal. 2011; 39 (1): 7 – 27.

CrossRef - Thomson J, Freudenberger K. S. Crafting Institutional Arrangements for Community Forestry. Community Forestry Field Manual 7. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization; 1997.

- Poffenberger M, McGean, B. Village Voices, Forest Choices: Joint Forest Management in India. Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1996.