The Impact of the Physical Elements of Persian Garden on the Persian Painting: A Selection of Tabriz’s Second School Paintings as the Case Study

Alireza Nazarnia1 and Zohreh Torabi1 *

1

Department of Architecture, Zanjan Branch,

Islamic Azad University,

Zanjan,

Iran

Corresponding author Email: zohreh.torabi@iauz.ac.ir

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.Special-Issue1.117

In Persian painting, as an abstract art, the use of garden has been as the way architects have used in designing the garden. However, the painter breaks different parts of the garden, so the viewer may move on the image. In this regard, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of Persian garden’s natural and man-made physical elements on painting art. For this purpose, a selection of Tabriz’s second school paintings, especially the paintings of “Khamseh Tahmasbi” and “Shahnameh Tahmasbi”, were analyzed accurately. This is an analytical-descriptive study; the library studies were used for collecting the data. The results showed that as far as form is concerned, these paintings picture all the natural and artificial physical elements of Persian Garden exactly like its architectural expression.

Copy the following to cite this article:

Nazarnia A, Torabi Z. The Impact of the Physical Elements of Persian Garden on the Persian Painting: A Selection of Tabriz’s Second School Paintings as the Case Study. Special Issue of Curr World Environ 2015;10(Special Issue May 2015). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.Special-Issue1.117

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Nazarnia A, Torabi Z. The Impact of the Physical Elements of Persian Garden on the Persian Painting: A Selection of Tabriz’s Second School Paintings as the Case Study. Special Issue of Curr World Environ 2015;10(Special Issue May 2015).

Available from: http://cwejournal.org?p=762/

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 2014-11-14 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 2014-11-14 |

Introduction

The Persian Garden is a cultural, historic, and physical phenomenon in the territory of Iran. In addition, the Persian Garden had a significant effect on other areas of Iranians’ arts such as carpentry, calligraphies, painting, Islamic philosophy and so forth. Because of the extent of this phenomenon, a wide range of experts inevitably deal with the Iranian garden. It has been showed off not only in physical and most practical forms of art such as carpentry, but also in most intellectual and imaginative forms such as musical expression. (Ansari et al., 2012) Accordingly, the miniatures in Iran try to connect the observer to the material and objective world. It is interesting that the garden has been the stuff of painter to establish the connection. Hence, the paintings have been a place to show the natural and man-made physical elements of Persian gardens objectively and subjectively. (Shahcheraghi, 2011)

This study aims to evaluate the impact of Persian garden’s natural and man-made physical elements on miniature art. In this regard, a selection of Tabriz’s second school miniatures, as the peak of painting evolution in Iran, was analyzed accurately. This is an analytical- descriptive study; the library studies were used for collecting the data. The selection of images has been based on the subject of study (paintings in Safavid era, Tabriz’s second school). This study assumes that with a deep and masterful understanding of color contrast composition and application, the painters tried to illustrate the around world with images. Meanwhile, they depicted remarkable features of Persian Garden in the images. This paper is organized in three parts. Initially, based on reliable sources and researches in the field of Persian garden display in art history, the effective areas of Persian garden in painting have been investigated. Their characteristics have been expressed through visual analysis of paintings.

Then, the Tabriz’s second school miniature art and the reasons for its rise and flourishing are expressed. Also, two outstanding versions of this school, in Safavid era, named Shahnameh Tahmasbi and Khamseh Tahmasbi are introduced. The physical features of Persian Garden are proposed in two natural (water system) and architectural categories (main building, palace, and decorative elements). They are compared with some selected paintings from Shahnameh Tahmasbi and Khamseh Tahmasbi. Finally, based on the obtained results, the aspects of paintings affected with Persian gardens are introduced and the Persian garden’s physical and artificial elements display on the paintings are discussed.

Materials and Methods

Display of Garden in Persian Miniature

During the cultural history of Iran, the Persian Gardens’ physical and semantic elements have been represented in several miniature works. Burckhardt argues that the function of traditional Iranian miniature shows a glimpse of the Persian garden in the world. He also believes that Iranian painting, in the traditional sense, is realistic -i-e- its emotional aspect strongly reflects the true nature of things. Besides, the animals and plants in miniature scenes are not merely imitating nature. Rather, it is an endeavor to depict the nature of heaven and the initial creation and nature, the sublime, and the heavenly paradise which have actuality at this moment in the fantasy world or instance universe. Similarly, the color of the mountains, clouds, or sky is unique and is different from natural colors. This oneness and uniqueness refers to the kingdom of heaven. (Burckhardt, 1997) Hence, some researchers have called Iranian miniatures as imagination gardens. Thus, discovering miniature aesthetics somehow helps synchronization with nature and poetic content and literary. (Kevorkian et al., 1998) It should be said that the link between Persian literature and painting has caused the Iranian miniature reach to aesthetic excellence. However in Iran, the painting has not been independent like other arts (especially painting art in the West) and it has served to the literature. (Javadi, 2004) So, the link between garden and painting can be recognized in two general areas:

The Miniatures with Complete Design of Persian Garden

From formal perspective, these paintings show Persian garden design exactly like its architectural expression along with all the natural and man-made elements. In these miniatures, the peripheral wall of enclosed garden, building entrance, the main palace, culverts, garden ponds and waterfalls, flowers and plants, trees, and birds can be seen with an order and expression typical of the Iranian miniatures. These miniatures are generally created for illustration in the books with love, mystical, war, hunting, party, outing in the garden, or religious themes in literature, especially in art works such as Shahnameh Ferdowsi, Manzoome Nezami Ganjavi, Shahnameh Tahmasbi, Khamseh Tahmasbi, and other famous poets in Iran. (Javadi, 2004) The Persian miniature has many visual features. Space is also one of the most striking characteristics of this art. The Iranian artist has applied various visual schemes to create this space and reach his/ her desired result. (Goudarzi et al., 2012) Even in the paintings with uniform and connected space, the miniature spatial view with its two-dimensional feature is distinguished from surrounding three-dimensional space. As a consequence, the space itself shows another universe which is connected with a consciousness other than ordinary human consciousness. (Burckhardt, 1997) In other words, it can be said that in this type of Persian miniatures, Persian Garden is fully displayed with all its details. However, considering the miniature qualities, the events occur in actual but not necessarily physical way and direct the viewer into a world that Iranian Muslim philosophers have called it the “imagination world”. (Ardalan, 1974) For example, in Persian paintings, the trees in garden with abstract forms and simultaneous display of nature’s four seasons create the timelessness. The garden in Persian miniatures is not shown as true nature and artist tries to express a different view of natural elements in his/her painting. However, the viewers get a completely natural and effective sense of the garden and space. The vitality of seeing natural garden is created by watching at miniature garden. (Shahcheraghi, 2011) In the following, the paintings with almost perfect design of Persian Garden can be seen (Figure 1).

|

|

The Miniatures Display Part of A Garden, its Elements and Activities Within it

Miniatures are appropriate documents to investigate various features of Iranian Gardens. In some of the these paintings, some aspects of Persian Garden such as palace space have been shown which today there is no sufficient evidence about it. (Soltanzadeh, 2008) These works depict the stories which are narrated in verse or prose texts. Generally, it can be said that after elements such as flowers, plants and trees which are the identity of a garden, the fountains, ponds and streams are the most important elements in these paintings which illustrate garden space in the mind of the viewer. Also, palaces and tents in the garden are displayed in some of the works. Since the Iranian painting is creative painting and it is not an imitator of nature, it is not dependent on reality. It does not intend to achieve realism. Rather, it describes the reality ideally and far from the real world. (Sahi, 2005) Hence, even in the drawing of the components and elements, depending on the style of the painter in each historical period, the appearance and characteristics of the details are different. For instance, in the following example and its visual analysis, the paintings can be seen that contain the elements of a garden or activities within it. (Shahcheraghi, 2011) (Figure 2)

|

|

The Persian Paintings of Tabriz’s Second School (Safavid Era)

The beginning of tenth century AD coincides with the formation of Safavid powerful government. First Shah Ismail (930-906 AH) was art lover. After repelling the enemy and establishing peace in the country, he gathered many artists and craftsmen in the capital, Tabriz. The Tabriz’s painting school was formed under the auspices of Safavid government and based on the artistic achievements of three schools: Shiraz’s painting (Timurid and Turkman period), Turkman school (Tabriz), and Herat school. Shah Ismail's main legacy was formalizing the Shi'a religion in Iran. This created homogeneity and unity in the visual arts of Iran and added the prosperity and wealth of Tabriz miniatures. Shah Tahmasb, like his father, was an art lover and had a major contribution to the development and support of Tabriz miniature school. In the first half of his reign (957- 930 AH), he paid more attention to art and gathered the skilled artists and artisans in his painting workshops. The true flourishing of Tabriz painting school occurred in the late third decade in tenth century AD. (Ansari et al., 2012) Some curtains clearly reflect the influence of Herat miniature and combination of local traditions and Behzad style. All together, these issues led to the establishment of Tabriz’s Safavid School. (Ashrafi, 2005)

|

Table 1: An introduction to a selection of Shahnameh and Khamse Tahmasbi’s paintings Click here to View table |

Description of Works

Khamseh Tahmasb Version

It is the second major project of Tabriz school paintings in Safavid period. This work was prepared by Shah Mahmoud Neishabouri under the support of Shah Tahmasb in Tabriz in 946 -949 AD. Its miniatures were drawn by a group of prominent artists such as Mir Seyyed Ali. Some historians believe that the Shah Tahmasb’s Khamse is the most exquisite work of the tenth century AD in Iran. (Binion, 2008) In its paintings, the landscapes, colors, and sculptures are special to Tabriz style. Its balanced configurations are consistent with the Herat style. Most of the compositions related to outdoors scenes such as garden and the court scenes show the court of Shah Tahmasb. (Azhand, 2005) This work has 17 paintings; 14 paintings were drawn in the time of writing the work. The size of its papers is 25.4 in 36.8 centimeter. This work is preserved in the Britannia Museum.

Shahnameh Tahmasbi Version

Perhaps the most magnificent and most detailed project conducted in Tabriz School during the Safavid period is Shahnameh Shah Tahmasb which known as Houghton Shahnameh. This work was ordered in 928 AD by Shah Ismail as a gift for his son, Tahmasb. It was conducted by Soltan Muhammad and Behzad. Narrated by Boudaq, the secretary, this work lasted twenty years until the year 950 AH. (Azhand, 2005) Its size is 47 in 31.8 centimeter. It consists of 759 papers and 258 paintings. It is unique in terms of content and glory. Due to showing unique images of buildings, textiles, and decorative arts of Safavid era, it is one of the rare cultural relics of tenth century. From the paintings, 118 paintings are in Iran and others are in the abroad museums. (Ansari et al., 2012)

Display of Physical Elements of Persian Garden in the Tabriz Second School Miniatures

Natural Elements of Garden

Water System

In the Persian garden, water is used not only for irrigation of garden plants, but also its conceptual, poetic, and artistic use has adorned the atmosphere of the garden. With its presence, it creates freshness, vitality, movement, and beauty. Ruy Gonzáles de Clavijo, the ambassador of the Kingdom of Spain in the middle of fourteenth century, described the Rose garden as: “High wall surrounds the garden where the environment is about one milestone. The garden is full of trees, except the lemon and Citron. Six large ponds can be seen in the garden. A large river flows from one pond to another”. (Gonzalez de clavijo, 2001) Here, five great streets have been constructed. The shady trees are planted on their sides. Their feet have been paved into a prestigious platform. (Wilber, 2011) (Figure 3) In the Persian garden, the pond or pool was used to reflect the beauty of the environment (Figure 4). There are pools and ponds in different parts of garden, in front of the palace, and interior spaces (Figure 4). In the 2, 3, 6, and 8 paintings, the form of water movement in the garden has a special and specific system that actually represents the geometry and structure of the garden architecture in that area. In these figures, the water current in the garden has a regular movement path on the pavement of garden path that shows direct and may be rather long movement axis (Figure 5). As the pictures show, the pools are seen as combined circular, rectangular, octagonal, and polygonal types. The pools have small sizes, probably because there remain sitting areas around them. There are also often birds like ducks and swans (Figure 6). The fountain in pools and ponds are used to make more attractive the space of the garden in all historical periods. A simple example of these fountains can be seen in the Fin Garden ponds (Figure 4). There is a small fountain in the middle of the ponds in the paintings 1, 3, 6 and 9 and there is a large fountain in the paintings 2 and 8; water flows from the top or sides. These fountains have ornamental shapes and golden colors. (Ansari et al., 2012) (Figure 8)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Architectural Elements of the Garden

The Palace and Main Building of the Garden

Palace is any excellent monument, pergola over the building, and summer room. It is also a terrace is covered by dome and its surrounding is open. (Dehkhoda, 1973) The maximum number of historical gardens in Iran has a palace or pavilion in the middle of garden (Figure 9). A more great building with various governmental and ceremonial functioning is in the center of the garden, such as Chehelsotoon Esfahan Garden and Hashtbehesht Palace in Esfahan. (Shahcheraghi, 2011) (Figure 9) In the paintings 1, 4, 6 and 7, the main architecture of the garden includes a palace and buildings surrounding it. The palaces have a main terrace where King, Prince, and their relatives sit there. The palace is located in the platform above courtyard. The pyramidal tower on the palace that was common in the Timurid period is seen in the miniature, too. (Lockhart et al., 2008)

|

|

In front of the main terrace, there is a pool and a place for the courtiers. The entrance to the main porch is in the middle and on the steps in front of it. According to the drawing of the palace, the plan is not obtained. Although, axonometric perspective was somewhat common in Timurid period for illustrating some of the monuments, a precise plan cannot be obtained from the images. According to images, however, it can be suggested that these palaces have square, rectangular, or octagonal plans. (Soltanzadeh, 2008) (Figure 10)

|

|

The Decorative Elements of the Garden

there are very few buildings date to Shah Tahmasb period. However, the residues of a palace belonging to the year 1560 AD / 968 AH at Nayin still have full and rich decorations. There is new decorative style on the largest porch where a thin layer of white plaster is carved. The walls above the plinth show sceneries of royal hunting, polo, courtly entertainment, love issues of Nezami and Jami, and verses of Hafez. The smaller parts are filled with complex network of crescent shapes on the ceiling, Chinese Dragon, Phoenix, and duck; there are groups of octagons at the top. (Brand, 2004) Plaster work and mirror work was common in the Safavid era. Another common decoration was mosaic and seven color tiles. There were used in many buildings, especially in outer view of the palaces. (Lockhart, 2008) (Figure 11) One of the outstanding features in the Persian painting is their decorative forms and motifs. These decorations are seen in various types such as geometric designs, arabesque designs and animal shapes and designs:

A. The geometric decoration is seen in regular or irregular shapes in the courtyard pavements, on the wall, internal and external appearance of the palace and building in the garden, latticed and woody windows and doors, inscriptions of porches, entrances and arches.

B. Arabesque design is seen as stylish plants and interwoven geometric lines on decorative frames in the porches, arches, inscriptions, wall paintings of the palace, rest places, carpets and even on the clothing (Figure 12).

C. Animal shapes and designs are seen as images of ducks, lion, deer, monkeys, and marine birds which are among the branches of plants alone or in combination with each other on the palace wall paintings; phoenix can be seen on the terrace roof in the painting one (Figure 12). Regarding the origin of animals’ drawings formation in paintings, it can be pointed out that: the Chinese art and painting influenced Iranian arts in the early Timurid and Shahrokh era. The Iranian painters got acquainted with and even used various decorative Chinese motifs such as dragon, phoenix, pelican, and real or imaginary animals. (Pope, 1998) For example, the sphinx can be seen in the Nader Divan Beigi School’s entrance in Bokhara (tenth century AD) (Figure 13). On the other hand in the Safavid era, the artists followed ancient visual tradition of the Sasanian era and used the animal shapes and drawings in their paintings. However, the Sasanian art effect is evident after more than a thousand years in the walls of Safavid kings palaces in Isfahan and Qazvin. (Tajvidi, 1973) (Figure 11

|

|

|

|

|

|

Results and Discussion

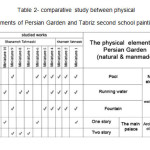

In the cultural history of Iran, the Persian Garden features have been presented in different miniatures. Studying the selected images in the miniatures of Khamse Tahmasbi and Shahnameh Tahmasbi, two prominent works of Tabriz second school in Safavid era, implies that these works show Persian garden design with all natural and man-made physical elements. The fence, building entrance, main palace, interior building, culverts, ponds, flowers and plants, garden functions and activities within it with regular order and special expression of Iranian painters. In the Iranian painting, the space components are always full, but the total atmosphere is rarely perfect. Also in the investigated works, the total composition is not immediately seen. The look of viewer goes from one part to another and from one plan to another plan and enters gradually into the two-dimensional space of the painting. There is no need to portray events. Several small trees remind the viewer of a landscape. The balcony view in a palace is fully but not totally pictured. However, the totality of space can be understood from the unfinished work. The use of garden in the painting is as the use of architects in the design of a garden. However, in the miniature, the two-dimensional space has its own features and in three-dimensional space, the garden has different features. In the garden, the viewer can shift and move in different directions; while in the painting, the total page can be seen in a limited time. However, the painter breaks different parts of the garden, so the viewer may move on the image. All in all, it can be said that after elements such as flowers, plants, and trees which are the identity of a garden, the fountains, ponds and streams are the most important elements in these paintings which illustrate garden space in the mind of the viewer. In addition to this, palaces and tents in the garden are displayed in some of the works. Since, the Iranian miniature is creative one and it is not an imitator of nature, it is not dependent on reality. It does not intend to achieve realism. It describes the reality ideally and far from real world. Hence, even in the drawing of the components and elements, depending on the style of the painter in each historical period, the appearance and characteristics of the details are different.

|

|

References

- Ansari, M; Saleh, A. A comparative study on Tabriz’s second school painting and Persian Garden in Timurid and Safavid era. Negareh Science-research quarterly, 22 (6), 6-17(2012).

- Ardalan, N. New creation. Arts and Architecture magazine, 25 (6), 36(1974).

- Ashrafi, M. Evolution of the sixteenth century Persian miniature (Academy of Art, 2005).

- Azhand, Y. School of Painting in Mashhad, Ghazvin, Tabriz (Academy of Art, 2005).

- Binion, L., Wilkinson, J. and Gary, B. The history of painting in Iran (Amirkabir, 2008).

- Brand, B. Islamic art (Institute of Islamic Art, 2004).

- Burckhardt, T. An introduction to principles and philosophy of Islamic art: the spiritual art principles (Office of Religious Studies, 1997).

- Dehkhoda, A. Dictionary (Tehran University, 1973).

- Gonzalez de clavijo, R. Narrative of the embassy of Ruy Gonzalez de clavijo to the court of Timour at Samarcand (Asian Educational Services, 2001).

- Goudarzi, M; Mozaffarikhah, Z. A Survey on space in the Persian miniature with emphasis on a selection of Behzad’s works. Two Quarterly of Islamic Art Studies, 16 (8), 7(2012).

- Javadi, Sh. Landscapes in the miniature of Iran. Scientific Quarterly of Baghnazar, 1(1), 29(2014).

- Javaherian, F. Persian garden: ancient wisdom, new perspective (Tehran contemporary museum, 2004).

- Kevorkian, A.M., Siker, Z.P. Garden of Imagination in seven centuries of Persian miniatures (Farzanrooz research, 1998).

- Khansary, M., Moghtader, M. and Yavari, M. Persian Garden: a reflection of Heaven (Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization, 2004).

- Lockhart, A., Jackson, P. History of Iran: Safavid era (Jami, 2008).

- Nayima, G. Persian Gardens (Payam, 2006).

- Shahcheraghi, A. The paradigm of paradises: recognition and recreation of the Persian Garden (Scientific Information Database, 2011).

- Soltanzadeh, H. Architecture and urban spaces in Persian painting (Chahartagh, 2008).

- Pope, A. The course and forms of painting in Iran (Mola, 1998).

- Stewart, C.W. Persian Paintings: Safavid era versions (Cultural publication, 2006).

- Stierlin, H. Islamic Art and Architecture: from Isfahan to the Taj Mahal (Thames & Hudson, 2002).

- Sahi, M. The nature of water, wind, earth and fire (Academy of Art, 2005).

- Tajvidi, A. Persian painting from the most ancient times until the Safavid (Ministry of Culture and Art, 1973).

- Tehran contemporary Art Museum. Masterpieces of the Persian Painting (Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in association with the institute for Promotion of Visual Arts, 2005).

- Wilber, D. Persian gardens and their palace (Scientific and Cultural publication, 2011).