Environmental and Landscapes Design in Archaeolandscapes by Using Remote Sensing

Firoozeh Agha Ebrahimi Samani1 * and Behrang Bahrami1

1

Department of Environmental Design,

Graduate Faculty of Environment,

University of Tehran,

Tehran,

Iran

Corresponding author Email: fsamani@ut.ac.ir

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.3.17

From the past, the combinations of the natural structures and the human features have created a specific cultural archaeolandscape. Therefore, the Environmental design in these landscapes have been presented through the main idea of “the passage of humans in the nature during over centuries” .In the new paradigm of integrated conservation in cultural landscapes, archaeological sites and buildings are evaluated in a wider range, and considerable attention is paid to them in the natural context. Recognizing the Connection between heritage and peoples over the time by focus on Environmental data integration, guide to find the destruction reasons and also guide us for best conservation. Therefore, archaeological sites, besides environmental factors, go under preservation and repair of the site and its environment. In this research, satellite data processing and image analysis have been applied besides environmental interpretations together with different scientific data. The result of these studies gave rise to comprehensive information to investigate and recognize the collocations of the ecological, archaeological and human structures from the past to the present and according to the purposes and strategies resulting from the wide environmental studies and the discussed principles of archaeolandscapes, attempts have been made to environmental design.

Copy the following to cite this article:

Samani F. A. E, Bahrami B. Environmental and Landscapes Design in Archaeolandscapes by Using Remote Sensing. Curr World Environ 2015;10(3) DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.3.17

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Samani F. A. E, Bahrami B. Environmental and Landscapes Design in Archaeolandscapes by Using Remote Sensing. Available from: http://www.cwejournal.org/?p=13096

Download article (pdf)

Citation Manager

Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 2015-09-28 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 2015-11-26 |

Introduction

The term “cultural landscape” embraces a diversity of manifestations of the interaction between humankind and its natural environment and about ideas and meanings, concepts and interpretations, dynamics and dialogues. Cultural landscapes are those where human interaction with natural systems has, over a long time, formed a distinctive landscape.

Then Cultural landscape is a complex phenomenon resulting from both natural- geographical and social-cultural processes and its approaches focus on mosaics of land uses/ecosystems at broader spatial scales. Main objectives include cultural and scenic values, as well as biodiversity and economic productivity, and focus on landscape composition and configuration (Bender et al. 2009).

Cultural landscapes also exist in people’s memories and imaginations and are linked to place names, myths, rituals and folklore.

The art effect in cultural landscape, for the archaeologist, is important; for historians, the visual or written document of landscape is primarily important; for the artist or tourist, mainly the associative value of beautiful scenery. It is increasingly apparent that the historical identity of individual landscapes is emphasized. Memories and associations are taken away in the mind of the viewer of a landscape. Through the preservation approach the landscape itself remains as a lasting memorial to the past. Cultural landscapes are very diverse and archeological landscapes are just one of them. Managing archeological landscapes requires many issues to be addressed, so an interdisciplinary approach is needed that covers history, art, geography, architecture and landscape architecture, archaeology, anthropology, legal studies, ecological sciences, social sciences, including town planning, communication and marketing, sociology, financial management, interpretation, training and education, as well as the various uses of landscape, such as agriculture, forestry, industry or tourism A cultural landscape may be directly associated with the living traditions of those inhabiting it, or living around it in the case of some designed landscapes like gardens. These associations arise from interactions and perceptions of a landscape; such as beliefs closely linked to the landscape and the way it has been perceived over time. These cultural landscapes mirror the cultures which created them (Fig.1) (Taylor, 2008).

Cultural landscapes are at the interface of culture and nature, tangible and intangible heritage, biological and cultural diversity –they represent a closely woven net of relationships, the essence of culture and people’s identity... they are a symbol of the growing recognition of the fundamental links between local communities and their heritage, humankind and its natural environment (Rössler, 2006).

|

|

In fact, cultural landscapes grow and survive in the range of time and place. From the past human construction in nature has been under the influence of the process in development of social life, natural and historical events that lead to create cultural landscapes. These landscapes connect the former natural – historical issues to the future ages and are presented by their universal distinctive features (UNESCO, 2009).

Then archeological landscapes can be seen as the repository of collective memory. Inspirational landscapes may become familiar to people through their depiction in paintings, poetry or song. But since the advent of industrialization and with global change, many people have realized that they have lost their spiritual connections with, and in, the landscape (Fig.2).

|

|

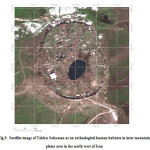

Archeological cultural landscapes often reflect specific techniques of sustainable human land-use, considering the characteristics and limits of the natural environment they are established in, and a specific spiritual relation to nature at the past (Fig.3).

In these sites, heritages as non-renewable natural resource, refers to the past anthropogenic and natural changes in the cultural landscape. Ecological and archaeological studies including exploring and exploiting the past landscapes have raised the awareness of preservation of nature and heritage. Contemporary archaeological sites are the products of predominantly man-made undertakings (Saruhan Mosler, 2012).

|

|

According to the new paradigm of comprehensive environmental protection of historical-natural perspectives, they are designed in the form of site museums. In the site museums, ruins, ancient buildings and monuments are considered as parts of the environmental components in the natural environment. In addition, ecological structures of the area such as the height and shape of the earth, rivers and surface streams and underground water (fountains, aqueducts, etc.), vegetation and land use in forms such as agricultural lands, gardens, natural indigenous forests and meadows, as well as soil texture and other characteristics of settlements, industries, accesses, fields, gardens, etc., are under environmental protection and restoration.

Materials and Methods

Iran plateau is a high land but its edges include much more elevation heights than those of the central areas. Considering the geomorphologic features and landforms of mountainous areas surrounding the Iran plateau, an upper- lower correlated system can be seen which is influenced by the different but yet correlated and connected distribution of natural resources such as water, vegetation cover, wild life, etc. In this correlated systems due to the relation between topography and moisture contents, which caused significant diminished temperature, climatic condition and plants covers. The abundance of water resources in mountains creates appropriate pasture in rugged levels as well as the flat amplitude plains (Beck, 2003).

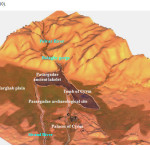

Although this plateau is a high land with several mountain ranges, and hinter land playa and lakes, but its marginal zones (Alborz and Zagros) are much higher where surrounding a vast territory with Islberg- type peaks and wide plains forming an upper- lower correlated systems (Fig.4) (Heydari, 2007).

Since ancient time, the natural shape of Iran with various specifications has provided human inhabitants in valleys, mountains, plains and river banks. Studying the historical geography and the relationship between civilization with capabilities, potential and the resources of each country shows that ancient people have acquired their initial information from nature and have applied their adopted knowledge in designing and making their own shelter (Beck, 2003).

Most of the ancient villages and human habitats in Iran, area have been formed in inter mountain plains which have the privilege of altitude, water and pasture on one hand and on the other hand they are away from high elevations, ice and snow covers.

These varieties of lifestyle in mountainous plain areas have caused sound reaction among their inhabitants.

|

Figure 4 Click here to View figure |

The signs of such a reactions, which are harmonious to the upper- lower nature, can be seen in Persian domestic decision making from the thousand years ago for seasonal migrations which itself is in compliance with nature generatively or spatial planning and finding locations for settlement in the scales of valleys, heights and plains (Irani Behbahani et al. 2008; Kruckman, 1987).

For example, considering the natural structure in the Marghab plain, next to Polvar-Sivand ancient river valley is a combination of the "High Zagros" mountain range and between mountain plains. This mountain plain region contains permanent-seasonal flows of Polvar-Sivand River and its several branches.

This has provided proper natural conditions for different types of native plants to grow. The aforementioned river has a permanent flow which snakes through northern parts of the Marghab plain and archaeolandscape of Pasargadae belong to Great Achaemenid civilization of 560-330 BC. (Fig.5).

|

|

The presence of various climatic features and the geographical natural structure of upper (heights), middle (plains) and lower (river) areas have given birth to several different ecosystems in mountains, between mountain plains and river sides (Bahrami et al. 2014).

Since archeological landscapes embed tribal values of people during history, they are always attractive to tourists. Lack of planning and design for these landscapes, also urban and transportation development in vicinity of them have led to their gradual degradation.

The global environmental movement is interested in archeological cultural landscapes because many are important for nature conservation and may contain habitats valuable to the conservation of biodiversity. Even some designed landscapes are now considered important gene pools (UNESCO, 2009).

|

|

Continuous structure of landscape and their entanglement with archaic and natural elements created a new approach toward archaeolandscapes conservation along with modern tourism development.

This approach enabled archaeolandscapes planning in the framework of open air museums.

Protection of these landscapes can contribute to modern techniques of sustainable land-use and can maintain or enhance natural values in the landscape. The continued existence of traditional forms of land-use supports biological diversity in many regions of the world. The protection of traditional cultural archeological landscapes is therefore helpful in maintaining biological diversity.

Besides anthropogenic and natural processes appearing in the course of time, the archaeological activities conducted on the sites have changed the visual, physical and spatial appearance of the site and its landscape. On the one hand this has frequently led to the deterioration of the site and surroundings lessening its aesthetic values, but on the other hand, inevitably it has opened a wide scope of facts about past cultures. In this respect, the aesthetic situation of the site after the excavations is always very critical.

|

|

Archaeological sites are recognized as an important magnet point due to the growing public interest and consequently mass tourism. Hence, there is a demand for planning of new services and facilities to support the regional or local growth, as well as to reduce the damages and impacts of exploitation by means of integrated planning principles. Regarding the threats of exploitation of ancient heritage, De La Torre (1995) discusses that the archaeological heritage faces increased risk of destruction from unchecked development, new infrastructure systems, excessive visitation, and inappropriate interventions that attempt to preserve the sites for tourists. To reduce all these impacts, archaeological sites should be presented in their setting which requires an integrated planning and presentation concept for the usage of archaeological heritage as tourism and heritage concept are both inseparable terms (Saruhan Mosler, 2012).

The restoration challenge in archeological landscapes is partly natural and partly cultural. Thus, it goes beyond the field of natural sciences to integrate those from social sciences, the humanities and local knowledge, in a trans-disciplinary approach (Irani Behbahani et al. 2010a).

The outcome of doing and other parallel research on archeological landscape carried out by researchers, show the formation of archeological cities in Iran is in line with natural specification and constant environmental factors. What is common in all of the research is the engineering of the occupancies based on constant modern development. Undoubtedly, the experience of ancient people based on the sacredness of nature and potential of natural environment as well as their respect to these factors, has been the basis for the thoughts and ideas which made them to create garden in desert, damn in mountain and cultural and economic strategic roads and finally would make their occupancies in complete accordance with nature from mountain to plain.

A new approach

Integrated conservation to environmental design in archeological landscapes as open air museum

Integrated conservation is one of the new issues in protecting archeological sites. In this category the position of archeological monuments is evaluated in a wider domain called archeological landscape and these monuments are considered to be parts of the environment of the natural bed of these landscapes. In the new perspective we are given, archeological monuments placed along side the natural factors and ecological features are conserved and renovated.

Therefore recognizing the natural characteristics of the area such as elevation features, geomorphology, hydrology and hydrogeology (including springs and underground waters), plant features, land use (in the form of agricultural fields, farms and gardens and native jungles and other environmental features and their interaction with human life with their constant interference and settlements, industries, roads, farms, etc. gains major significance. These considerable studies reveal the ongoing changes of landscapes in the course of time. Because natural features all together create a dynamic context for the formation and completion of human-made features which in turn interact with above features and change.

Open air museums not only protect the monument and its natural context, but also they make the tourists to comprehend the changes in course of time and also to get familiar with excavation activities. In fact, these sites provide the tourists with both recreational and educational possibilities. However, the following process seems essential for best design of open air museum.

In this research and similar researches, different information including geology, botany, hydrology and hydrogeology, tectonics, region and etc. are provided in order to recognize the ecological specifications and natural structure of the area as well as identifying the role and influence of these structures in formation of human occupancies.

Corresponding of these informational layers leads to new results for structural relation. The relation between the environmental components causes potentialities that interprets and justifies the formation of human civilizations and his occupancies as ancient cities (Irani Behbahani et al. 2008).

Considering the location of the majority of archeological occupancies in natural landscapes and with their unique specifications and their wide range of studies from the view point of accessing to the ecological and geomorphologic structure as well as perceiving the mutual correlation between the parts of the environment in shaping and identifying the whole natural – historical collection, is essential for doing inter-disciplined studies in different fields and scales.

Results

Multidisciplinary Analysis of Nature, Culture and History in the Archaeolandscape

By expanding interdisciplinary methods and development of technology, software facilities have been at the service of scientific research. In the meantime, using radiometric telemetry and spectrum in researches related to natural – historical landscapes has a great importance in all over the world (Iannone, 2002).

In recent years, using satellites data in different scales and its syncretism with specialized field studies gave rise to comprehensive information to investigate and recognize the collocations of the ecological and residential structures from the past to the present. The use of radiometric and spectral distant-measurement in interdisciplinary studies like eco-archeology is of great importance. Distant-measurement data, and aerial and satellite interpretation can be used as a good device to recognize natural and artificial structures and structural phenomena.

Utilizing satellite analytical and evaluating system in completing the professional studies is absolutely necessary. In ancient cities where in spite of evacuation of modern population the stream of life still exists, reaching for an accurate model of living and nonliving of intersystem correlation lead the researchers to the causes of how these occupancies have formed. Moreover, these categorized and précised information which has usually been gathered by using the modern software systems and database will be analyzed and studied by experts in various scientific specialties (Kruckman, 1987).

Remote sensing data and image analysis are used as major tools in investigating natural formations and man-made structures (Bahrami et al. 2007).

Wilkinson (2003), mentions to the basic imaging system useful for the landscape archeology, while studying the application of this technique in the Near and Middle East In order to achieve the aim of this research, various integrated thematic datasets were used.

For example to design Pasargadae open air museum, through specialized processing of ETM+ and Quickbird satellite data, in different scales and study layers, the ecologic structure, landscape features, and the natural historical bed of the region was studied, and the most prominent features of the given natural-historical structure and the relations and interactions among them were specified in the framework of cultural perspective.

ETM+ and Quickbird remotely sensed data, have produced thematic images, significantly enhanced the understanding of archeological resources, localities, and their historical-evolution by geo-environmental variations.

Pasargad is situated in the Marghab plain with a landscape that is a combination of green cultivated fields, vast pasture lands, and sporadic villages, with some remnants of ancient buildings. This plain has an altitude of 1840m above sea level, rising to 1870m. In the northern and eastern sections it turns into low hills and plains, and is bounded to the south and southwest by the elevated areas of Bolaghy gorge (Bahrami et al. 2007) (Fig.8).

|

|

The Polvar river has a north-to-south flow direction within the Marghab plain, and gently meanders into Bolaghy gorge towards the south. Seivand is a part of the Polvar, and flows from Bolaghy gorge to the south. The presence of natural features and mountainous terrains in the west and southwest, and the hills in the north and east of the Marghab plain, have made it an enclosed space surrounded by natural partitions.

Undoubtedly, this and the availability of favorable land, water resources, and suitable defensive features, were important reasons for the selection as the setting for the capital of the first Persian Empire, the Achaemenian kings.

Based on photogeology and remote sensing image analysis, this region possesses special geomorphology with large farmlands, scattered villages and natural features. Extensive development of different geomorphologic features such as high escarpments and steep slopes close to lowlands, karstic caves, and structural deformations and dissected bedded units present a unique natural landscape (Fig.9).

|

|

The geomorphologic characters, deposited fine clayey sediments on flat plains of the area, and depth of groundwater level, vegetation cover, rate of vegetation growth, moisture content of the soil and its type all are having different reflectance and recorded electromagnetic emanations. These differences recorded in satellite images are the most powerful tools for delineating and separation of geologic environments. The alluvial coverage of the area indicates a high energy and flooding streams which have deposited alluvial type fan deposits containing detrital large grain clastic sediments with low context moisture and poor vegetation coverage. Marghab plain is a floodplain characterized by dendritic pattern drainage stream that recharges the surface waters into Bolaghy gorge which is the main run out system for Polvar River and Marghab plain (Bahrami et al. 2007).

The Polvar river in Bolaghy gorge follows a trellis pattern which is caused by weak zones in bedrock that differ in their resistance to erosion. The trellis pattern usually, indicates that the region is underlain by alternate bands of resistant features of same valleys are short narrow segments walled by steep rock slopes or cliffs. These are called “water gap” (Samani, 2002).

The river in effect, flows through a narrow notch is a ridge that lies across the course of the river. This narrow notch, before degradation had acted as a barrier or natural dam to form a water reservoir (local lake) on the upstream part (Marghab plain) where the Pasargadae is located (Fig.10).

|

|

The boundaries of the lakelet have been defined by geologic evidence, agronomic criteria, and processed satellite images, reveal differences in the texture of green vegetative cover in comparison to the general texture of the surrounding plain. Considering the existence of the lakelet in the western and southern areas, and the position and orientation of the Tomb of Cyrus the Great, it can be concluded that the original entrance road was different from the present location.

Discussions

Applying the different methods of studying, analyzing data, categorizing and deduction of findings in a complementary process leads to simulation of natural environment and ancient occupancy. In modern methods of studying natural – archeological landscapes, they utilize satellite analytical system in various environmental specialties. They also use the modern technology of telemetry for preparing database in GIS in process of this research (Iannone, 2002; Rences 1999).

Connection between different structures, guide the researchers to a path that finally make them find the destruction reasons of the occupancies through comparing the available information and cultural and archeological documents together with introducing a cultural view of the past. This also will lead them to remove the secret shroud and complication of the previous centuries and find reasonable answers for most of questions (Irani Behbahani et al. 2010 a).

At the present time, the presence of human beings as farmers, archeologists, or tourists also completes the concept of the cultural landscape of the region. Therefore, the plan for the open air museum has been presented through the main idea of “the passage of humans in the nature during over centuries”.

Based on interdisciplinary research, Pasargadae Open air museum has finally been designed further to determined degradation factors. The main focus was on conservation of ecological structures and archeological elements, so that the tourists will understand the origins of creation and the following changes and finally enjoy the visual/ spiritual contact.

In the presented plan, according to the purposes and strategies resulting from the wide environmental studies and the discussed principles of cultural landscapes, attempts have been made to present a plan, simple and harmonious with the surrounding view, which is useful in introducing the cultural landscape to native and non-native sustainable tourists.

References

- Ardalan, N. and Bakhtiar L., The sense of unity: the Sufi tradition in Persian architecture, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1979.

- Bahrami B., and Agha Ebrahimi Samani F. The role of environmental data integration for specifying conservative buffer zone in cultural landscape. International Journal on Technical and Physical Problems of Engineering, 6: 86-91(2014).

- Bahrami B., and Aminzadeh B. Discovering the ancient lakelet of the archeological site of Pasargadae in Iran. Environmental Geology, 53(1): 123-133 (2007).

- Beck, L. Use of Land by Nomadic Pastoralists in Iran. Middle Eastern Natural Environment 103:72-93 (2001).

- Bender, O., Evelpidou N., Krek A., and Vassilopoulos A., Geoinformation Technologies for geocultural landscapes, Taylor and Francis, UK, 2009.

- Heydari, S., The Impact of Geology and Geomorphology on Cave and Rock shelter Archaeological Site Formation, Preservation and Distribution in the Zagros Mountains of Iran. Geo archaeology: An International Journal, 22 (6): 653–669 (2007).

- Iannone, G., Annales History and the Ancient Maya State: Some Observations on the Dynamic Model. American Anthropologist , 68-78. (2002).

- Irani Behbahani, H., Bahrami B and Agha Ebrahimi Samani F (2010 a). Research project and introducing the cultural landscape of Takht- i- Sulaiman based on satellite database, University of Tehran, Tehran.

- Irani Behbahani H., Bahrami B., and Agha Ebrahimi Samani F. Multidisciplinary Analysis of Nature, Culture and History in the Archeological Landscape of Iran”, ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES, 7(3): 103-116 (2010 b).

- Irani Behbahani H., Bahrami B., and Agha Ebrahimi Samani F. Research project and introducing the cultural landscape of Bishapur based on satellite analyzing database, Cultural Heritage Organization, Tourism and Handicrafts, Tehran, 2008.

- Kruckman L., The role of Remote Sensing in ethno historical research, Wiley, New York, 1987.

- Rences N., Remote Sensing for the earth sciences, Manual of Remote Sensing, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1999.

- Rössler M., World Heritage Cultural Landscapes. Landscape Research, 31(4): 333-353, (2006).

- Samani B., Geomorphology and Tectonoeustatic Evolution of Zagros Folded Belt, East Nazil co., Tehran, 2002.

- Saruhan Mosler A., Establishing landscape design principles for archaeological sites by means of examples from West Anatolia, Turkey, 2012.

- Taylor K., Landscape and Memory: cultural landscapes, intangible values and some thoughts on Asia, The Australian National University, 2008.

- UNESCO, Worldwide basic inventory /Register card Cultural Landscapes Verbania, IFLA: Cultural Landscape Committee, 2009.

- Wilkinson T. J., Archeological landscapes of the Near East, University of Arizona, Tuscan, 2003.