Consequences of Promoting Less-Populated Rural Areas to Urban Areas: A Case Study, Bushehr Province

Ali Bastin1 *

1

Department of Geography,

University of Tehran,

Tehran,

Iran

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.1.11

Copy the following to cite this article:

Bastin A. Consequences of Promoting Less-Populated Rural Areas to Urban Areas: A Case Study, Bushehr Province. Curr World Environ 2015;10(1). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.1.11

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Bastin A. Consequences of Promoting Less-Populated Rural Areas to Urban Areas: A Case Study, Bushehr Province. Curr World Environ 2015;10(1). Available from: http://www.cwejournal.org/?p=9120

Download article (pdf)

Citation Manager

Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 2015-03-15 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 2015-04-15 |

Urban and rural areas are two systems interacting in the regional development process (Liu & et al, 2013; Chen et al, 2010). Almost half of the world's urban population and about a quarter of the world's population live in village-cities (Satterthwaite & Tacoli, 2003). However, most researchers and policy makers have almost all been fascinated by the challenges and problems of large cities and metropolitan. rural planners and researchers have traditionally focused on rural studies and agricultural areas. In the meantime, smaller urban settlements have been neglected (Kammeier, 2002).

The modified law of Iranian Administrative divisions has greatly altered the pattern of settlement in recent decades (Rezvani et al, 2009). In many areas, the policy of promotion of villages to cities converted many rural areas to urban areas, particularly in the last two decades (Akbarian-Ronizi, 2007). The number of cities increased from 199 in 1956 to 1016 in 2007 and 1139 in 2012 (Iran Statistics Bureau, 2011).

The promotion of rural areas to urban areas is based on urban functions in rural development (UFRD) strategy which considers the promotion of village to city as a solution for development. The general assumption is that small towns play a role in national, regional and local developments (Herve, 1996). This is why an effect of accelerated urbanism on spatial structure and population has been a growing number of cities in Iran by promoting rural areas to small town during the last half century. The highest increase in the number of cities occurred in a 15-year period from 1997 to 2011. In this period, a city was emerged and added to the urban system every 10 days. Some of them were villages promoted to cities because of population growth to the population threshold. While, most of this newly founded towns were villages promoted to cities, despite the lack of minimum population requirements, for various reasons, such as demand of local people, special geographical and political location, central divisions, and finally the approval of officials. This has been a clearly prominent phenomenon in the last two decades. The number of these non-standard cities is nearly one third of the cities in Iran (Zangane-Shahraki, 2013).

This paper evaluates the effects of promoting less-populated rural areas to cities in Bushehr province during 1996 to 2001 census. These effects are analyzed in economic, social, physical and urban servicing domains from the perspective of residents. Implicitly, the urban system of Bushehr province is discussed since 1956.

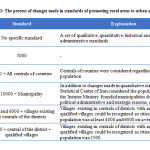

Criteria Required for Promotion of Rural Areas to Urban Areas in Iran

At different periods of population census in Iran, different definitions of city were presented. In the first census in 1956, the city was defined based on the counts of residents; all areas with more than 5 million residents were considered as cities, disregarding that whether there were municipalities and they were centrals. In the 1966 Census, the same population-based definition was used with some small differences in considering the centrals as cities. This definition was also considered in the 1976 census (Zanjani, 1997). From 1976 to 1983, those villages with more than five thousand people were promoted to cities. Subsequently, the municipality, the police station, and other institutions and municipal services were established in these cities. After 1983, the five thousand increased to 10 thousand. However, there were villages with a population of more than 10,000 which were still rural; the reverse is also true. There were areas with populations of less than ten thousand, but they were known as city. In such cases, political considerations were not ineffective (Mahdavi, 2002). From 1993 to 2010, an amendment was added to Article 4 of the Administrative Divisions of Iran, acknowledging that: the centrals of each district with any population as well as qualified rural areas (Article 4, Definitions of Divisions) can be known as city, if their population is at least 4000 and 6000 on average. Since 2010, this standard has again changed and the population standard was reduced to its lowest amount ever, 3500. In this period, all qualified district centrals and villages were promoted to cities. Table 1 lists the standards for promotion of rural to urban areas in Iran since the beginning of census periods. Obviously, the Administrative Divisions Law has considerably shifted from mere population standard to combined standards (population-administrative standards for centrals of counties and districts).

|

Table 1: The process of changes made in standards of promoting rural areas to urban areas Click here to View table |

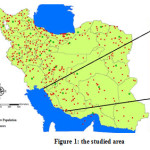

The Studied Area

Bushehr province is located in an area of 25,359.5 km2 (1.5% of total area of Iran) in the south west, northern 27° 14’ and eastern 50° 6’ to 52°58’ of Greenwich Meridian (Iran Statistics Bureau, 2011). The province is limited to Khuzestan and Kohgiluie and Boyer-Ahmad provinces from the north, to Persian Gulf and a part of Khuzestan province from the south, to Fars province from the east and to the Persian Gulf from the west. With more than 730 km of shared border with Persian Gulf, the Bushehr province is strategically, economically and tourism important (Pantea-Bootorab, et al., 2007). The cities studied here included 12 sparsely populated rural areas (5000) which have been promoted to cities followed by the relevant policy. It is noteworthy that, Alishahr is a newly founded city without any rural history; hence, it was excluded from the study.

|

Figure 1: the studied area Click here to View figure |

Analysis of Urban System in Bushehr Province

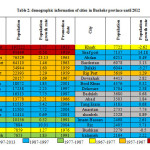

Until 1960, Bushehr Province was considered as a part of Fars Province as the seventh province of Iran. According to the official censuses, there were two cities in Bushehr Province until 1956, Bushehr and Borazjan; total population of two cities was 290,671. Rural population growth and physical development gradually began from 1956. In 1345, there were seven new cities in the Bushehr Province, all of which were promoted from rural to urban adopting new functions. From 1966 to 1976, Khark and Sa’ad-Abad were promoted to cities; hence, the number of cities became 11. Interestingly, no rural area was promoted to the city for a decade (1976 to 1986). In 1986 to 1996, two other villages were promoted to cities. However, the pace of change was slow. In 1996 to 2006, the process suddenly accelerated; 16 populous rural areas were promoted to urban areas. Hence, there were 29 cities in Bushehr Province at that time. Since 2006 onward, this trend continued to decline; in this period, seven villages were promoted to cities. However, the trend is expected to accelerate suddenly in the near future. Currently, there are 10 counties, 24 districts, 46 rural districts, 37 cities and 910 villages in Bushehr Province. The table below lists the demographic details of Bushehr province.

|

Table 2: Demographic information of cities in Bushehr province until 2012 Click here to View table |

Obviously, the population of 12 out of 36 cities is 37,468. The total urban population of Bushehr Province is 718,268; the studied cities account for 5.21% of the total urban population in the province. As shown in Table 2, 7 cities out of these 12 cities lack the minimum population standard (3,500); these seven cities were promoted for political reasons or special considerations.

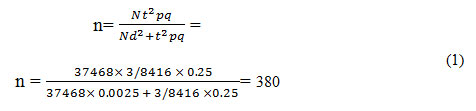

Methodology

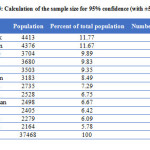

This descriptive-analytic study reviewed the results of population and housing censuses of Bushehr province from 1997 to 2013. Data was collected using questionnaires library studies. The studied group included the residents of those cities whose population was less than 5000; according to population and housing census 2012, total number of residents was 37,468 in those cities (Iran Statistics Bureau, 2011). To calculate the sample size, the Cochran formula was used. In this study, no estimate of sample population variance was available. Accordingly, the highest distribution of studied traits was considered (p = 0.5 and q = 0.5) assuming divalent variables. The sampling error probability < 0.05 and 0.05 probable accuracy (d) were also considered (Hafeznia, 2011). The sample size was 380 in 95% confidence level. The stratified random sampling was used in which the sample size is proportional to the studied group and its homogeneity or heterogeneity in each area of the study (Sarmad, et al., 2014).

|

Table 3: Calculation of the sample size for 95%confidence (with ±5% error) Click here to View table |

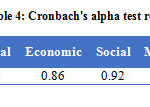

Data was collected by a 23-item questionnaire in a five-point Likert-type scale and distributed among the samples. The data was measured in a sequential scale. Hence, one-way T-test and utility range was used for data analysis in a 0.95 confidence level. Data was analyzed in SPSS, V20. The reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed using Cronbach's alpha; according to the following table, the reliability of parameters is at an acceptable level.

|

Table 4: Cronbach's alpha test results Click here to View table |

Results

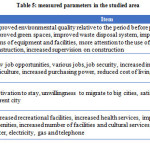

To evaluate the consequences of rural-urban promotion in the studied area, four physical, economic, social and urban servicing parameters were measured by the relevant items. These parameters are based on previous studies done on the subject (Zangane-Shahraki, 2013; Zangane , et al., 2014; Mohamadpoor-lima, et al., 2013; Barghi, et al., 2012; Firouznia , et al., 2012; Rezvani, et al., 2010; Ziatavana & Amir-Entekhabi, 2008; Goli, 2008; Shokui, 2007; Izadi-Kherameh, 2004).

|

Table 5: measured parameters in the studied area Click here to View table |

Demographics of the Studied Area

The results obtained from the questionnaire showed that respondents were 92% male and 8% female. Most respondents aged 30 to 40 years, accounting for 38% of the samples. In terms of marital status, respondents were 18% single and 82% married. In terms of education, respondents were 10% illiterate and under-diploma, 28% high school diploma, 32% undergraduate, 23% graduate and above, and 7% unknown. In terms of employment, respondents were 25% farmers, 13% fisheries-related practitioners, 54% active in servicing and administrative activities and 8% unknown. In terms of revenue, 13% earned less than 800,000 Tomans a month, 34% earned 800,000 to 1 million Tomans, 42% earned 1 to 1.5 million, 5% earned 1.5 to 2 million and 6% earned more than 2 million Tomans per month. It is noteworthy that, households are usually conservative about their monthly income, expressing incomes less than the original earnings. Nevertheless, the results show that most households have an average and average to low economic status.

Consequences of Promoting Less-Populated Rural Areas to Cities in the Studied Area Physical Effects

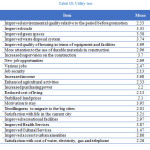

According to Table 6, the mean of items including improved roads, improved green spaces, improved waste disposal system, improved quality of housing in terms of equipment and facilities, and increased supervision on construction was higher than the expected standard. Therefore, their effects were positive. In fact, the respondents believed that promotion has improved the above items. Among the items of physical effects, ‘improved quality of the environment’ lacked a positive effect and the item ‘attention to use of durable materials for construction’ was also insignificant.

|

Table 6: physical consequences of rural-urban promotion in the studied area Click here to View table |

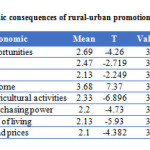

Economic Effects

Among the tested items, only the increased income (mean=3.68) was higher than the standard, suggesting a positive effect on residents. Other items were not considerably satisfactory. The stabilized land price (mean=2.1) was the most negative consequence of rural-urban promotion on citizens. The results of field studies also support this. It is noteworthy that the first psychological and economic consequence of rural-urban promotion is the staggering increase in the price of lands, particularly adjacent to the commercial sector, which lead to unhealthy economic relationships and activities of land and housing speculators. Field study results showed a direct relationship between the increase in the price of residential and commercial land in sparsely populated cities of Bushehr Province and factors such as distance from the central of the county, the physical texture and borders of these cities. In the cities near the central of the county (as Delaware), the price of land, housing and commercial units has so increased that, at some points, it is equal to the central of the county.

|

Table 7: Economic consequences of rural-urban promotion in the studied area Click here to View table |

Social Effects

As the results obtained for social effects show, the mean of the item 'motivation to stay’ is the highest (mean=3.95 and T=11.73), while the mean of the second item ‘unwillingness to migrate to the big cities’ is lower than the expected level .3 This means that most members of the sample group tend to migrate to the big cities of the province rather than middle cities. In the urban system of Iran, particularly Bushehr province, middle cities are less important in attracting immigration. In fact, the residents of the studied cities tend to stay in their current city; in case of decided immigration, they tend to migrate directly to provincial capitals and major cities. The results for ‘satisfaction with living in the current city’ concluded that residents are satisfied with living in the current city. This could be because of their expectations, attitudes and perceptions of urban life. Despite all the problems caused by rural-urban promotion, particularly in the economic indicators, residents are subjectively satisfied with living in the city, which is a sociological discussion.

|

Table 8: Social consequences of rural-urban promotion in the studied area Click here to View table |

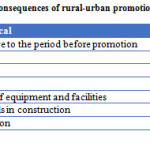

The Effects of Urban Servicing

The last parameter is urban servicing. The highest T-score is related to health care services (6.21). The item ‘improved recreational facilities’ (mean=~3) is almost satisfactory. Other items do not show a considerable improvement in the studied villages (mean=<3). The item ‘improved access to the urban facilities’ (α=0.057) is significantly higher than the critical value and it is not significant. In general, it can be concluded that the negative effects of rural-urban promotion are more than its positive effects.

|

Table 9: Consequences of rural-urban promotion in the studied area Click here to View table |

According to the above table, cultural services which are a characteristic of modern urban life do not show any improvement in the studied cities. Accordingly, the satisfaction with costs of water, electricity, gas and telephone has increased by rural-urban promotion, which also adds to the economic pressures on residents.

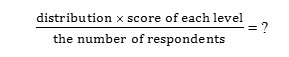

Utility Test of Items

By comparison of means obtained from responses, it is necessary to test the utility of items for each parameter. For this purpose, the range of utility (Bazargan , et al., 2007) was used. At this stage, the weighting method (valuation) was used to determine the score of items by calculating the mean of that item. As the formula shows, the score of items are determined by determining the distribution of responses for each item and determining the score of that item (Bazargan, et al., 2007).

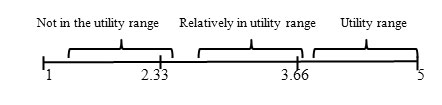

The questionnaire is scored in a five-point Likert type; in addition, the mean of items cannot be less than one. Therefore, the interval of utility range was 2.33. Moreover, calculation of scores determines the range to which scores belong.

The score ranging from 1 to 2.33 is not in utility range; the score ranging from 2.33 to 3.66 is relatively in utility range; finally, the score ranging from 3.66 to 5 is in the utility range. By multiplying each of these points by the number of items related to each parameter, the utility range is obtained for each parameter (Bazargan , et al., 2007). This method is based on comparison of means and based on one-sample T test. Table 10 presents the final results of utility test for each item.

|

Table 10: Utility test Click here to View table |

Out of the 23 items tested, only 5 items are in utility range, 8 items are relatively in the utility range and 8 items are not in the utility range. In addition, 2 items are insignificant. Comparison of the means show that social and physical effects of rural-urban promotion are better than the 2 other parameters. The results indicate that the economic effects are relatively not in the utility range.

Discussion

It is difficult to find two similar definitions of city suitable for all types of cities in different times and different societies to meet the needs of diverse and numerous empirical studies. One of the criteria upon which settlements are distinguished is population; population partly reflects the diversity and number of activities influencing the settlements and their extent. Because small towns are considered as one of the strategies of development in Iran, they have been promoted to urban areas since 1990s. Every year, a large number of the rural areas are promoted to urban areas, regardless of the population. Even since 2010, when the population standard has been reduced to its lowest amount (3,500) during the past one hundred years, numerous villages can be found yet with a population less than this minimum amount. In the studied area, the population of 7 villages was less than 3,500; however, they were promoted to cities for other reasons. It is noteworthy that these cities are usually weak in terms of physical view, land use planning, infrastructure and equipment, facilities and utilities, government agencies and civil institutions, administrative infrastructures, livelihood and many other aspects. Sometimes, there is no resemblance to the real concept of city from both population and other institutional, functional and physical aspects. These settlements are challenged by many problems, including:

- The growth of agriculture is not relative to other sectors.

- There are restrictions on industrial growth.

- Migration increases from villages to cities and provincial capitals.

- Unemployment and abnormalities increase in the structure of economy.

- Marginalization and poverty increase in the cities.

- Income and wealth are unequally distributed and specific problems of rural communities remain to exist.

Conclusion

The present study evaluates the effects resulting from promotion of less populated rural areas to urban areas in Bushehr Province from four physical, economic, social and urban servicing aspects. The results showed that rural-urban promotion has favorable outcomes (in the utility range) such as improved waste disposal system, improved quality of residential units, increased supervision on construction, stabilized population growth and motivated residents to remain. In addition, 8 items were relatively favorable (relatively in the utility range), including improved environmental quality, improved roads, improved green spaces, new job opportunities, various jobs, improved health, improved recreational facilities and satisfaction with life in the current city. While the promotion has failed in some economic, physical and servicing variables such as job security, promoted agricultural activities, increased purchasing power, decreased cost of living, the stabilized land price, controlled migration to large cities and provincial capitals, art and cultural facilities and satisfaction with costs of urban services. In general, the negative consequences of this process have been more than its positive consequences. Hence, it is necessary to consider revisions in the rural-urban promotion, because a change or gradual promotion leads to proper economic, physical, social and cultural contexts for formation of the city, while the sudden change without any provision makes the planning difficult for those who are involved in planning.

References

- Akbarian-Ronizi, S., 2007. the role and function of small town in rural development, Tehran: s.n.

- Barghi, H., Ghanbari, Y. & Seyfollahi, M., 2012. satisfaction of rural residents with rural-urban promotion. geography institute of Iran, 9(31), pp. 215-233.

- Bazargan , A., Hejazi, Y. & Eshaghi, F., 2007. internal assessment process. Tehran: Doran Press.

- Chen, Yufu; Liu, Yansui (2010). Characteristics and mechanism of agricultural transformation in typical rural areas of Eastern China: a case study of Yucheng city, Shandong province. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 20 (6), pp 545-553.

- Firouznia , G., Mosakazemi, M. & Sadeghi-Taheri, A., 2012. the effect of rural-urban incorporation. geography and development, Issue 25, pp. 79-96.

- Goli, A., 2008. consequences of rural-urban promotion. Issue 25, pp. 33-37.

- Hafeznia, M., 2011. an introduction on methodology in human sciences. 17th ed. tehran: samt.

- Herve, Michel (1996). The Active Citizenship as Decisive Element of the Sustainable Urban Development- the Experience of Parthenay. Utopias and Realities of urban Sustainable Development, Conference Proceeding, Turino- Barlo, European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, PP 251- 262.

- Iran Statistics Bureau (2011). Results of General Census of Population & Housing in 2011. Available at: http://www.amar.org.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=1828

- Izadi-Kherameh, H., 2004. rural-urban promotion and its role in rural development, Tehran: s.n.

- Kammeier, H (2002). Rural-Urban Linkages and the Role of Small and Medium Sized Towns in Development: Issues, Concepts and Policies. Workshop on Poverty Alleviation through Rural-Urban Linkages: The Role of Small and Medium-Sized Towns, Siemreap, Cambodia.

- Liu, Yansui; Lu, Shasha; Chen, Yufu (2013). Spatio-temporal change of urbanerural equalized development patterns in China and its driving factors. Journal of Rural Studies, 32, pp 320-330.

- Mahdavi, M., 2002. an introduction to rural geography of iran. tehran: samt.

- Mohamadpoor-lima, N., Noori-Kermani, A. & Alizad-Minabad, F., 2013. economic and physical factors of conflicts resulting from rural-urban incorporation. geography and environmental studies, 1(4), pp. 60-78.

- Pantea-Bootorab, S., Mirkazemian, M. & Fotovat-Roodsari, H., 2007. geography of Bushehr Province. national geological database of Iran.

- Rezvani, M., Mansourian, H. & Ahmadi, F., 2010. rural-urban promotion and its role in improving quality of life of local residents. rural studies, 1(1), pp. 33-65.

- Rezvani, Mohammadreza, Shakoor, Ali, Akbarian Ronizi, Saeedreza and Roshan, Gholamreza (2009). The Role and Function of Small Towns in Rural Development Using Network Analysis Method; Case: Roniz Rural District Estahban city, province Fars, Iran), Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 2 (9), PP 214-223.

- Sarmad, Z., Bazargan, A. & Hejazi, E., 2014. methodologies in behavioral sciences. 25th ed. tehran: Nashr-agah.

- Satterthwaite, D & Tacoli, C (2003). The Urban Part of Rural Development, the Role of Small and Intermediate Urban Centres, London: IIED.

- Shokui, H., 2007. new approaches on urban geography. tehran: Samt.

- Zangane , Y., Samipoor, D. & hamidian, A., 2014. rural-urban promotion and its role in regional development and urban system development. geographical studies on arid areas, 4(13), pp. 17-36.

- Zangane-Shahraki, S., 2013. promotion of rural areas to urban areas in a national level and emergence of raw cities. rural studies, 4(3), pp. 535-557.

- Zanjani, H., 1997. discussions and methodologies of urban planning- population. Tehran: urban planning and architecture research center.

- Ziatavana, M.-H. & Amir-Entekhabi, S., 2008. rural-urban promotion and its consequences in Talesh. geography and development, Issue 10, pp. 107-128.