A Study on the Bioresources of the Loktak Lake, Manipur (India) for Livelihood by the People Living in Five Villages Located in and Around the Lake

Corresponding author Email: jogesh100.2008@rediffmail.com

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.16.3.23

Copy the following to cite this article:

Laishram J. A Study on the Bioresources of the Loktak Lake, Manipur (India) for Livelihood by the People Living in Five Villages Located in and Around the Lake. Curr World Environ 2021;16(3). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.16.3.23

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Laishram J. A Study on the Bioresources of the Loktak Lake, Manipur (India) for Livelihood by the People Living in Five Villages Located in and Around the Lake. Curr World Environ 2021;16(3). Available From: https://bit.ly/3oOnM4H

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 09-11-2020 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 10-12-2021 |

| Reviewed by: |

Sudheer Padikkal

Sudheer Padikkal

|

| Second Review by: |

Satyapriya Rout

Satyapriya Rout

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Mohammad Oves |

Introduction

Loktak Lake lies in the southern part of the Imphal valley of Manipur state and is located between 93°46' and 93°55' E and from 24°25' to 24°42'N. Length of the lake is 26 Km and breadth is 13 Km and the lake is oval in shape. Its depth ranges between 0.5 to 4.58 m with average depth measuring 2.7 m. Loktak lake has been considered as lifeline of the people of Manipur because the lake plays an important role in the socio-economic and cultural life of the people of the state. The lake plays a significant role in providing ecological and financial security to the state and is the largest natural freshwater lake in the northeastern region of India. People residing in the periphery of the lake depends upon the resources of the lake for survival. In the year 1990 under Ramsar Convention the lake has been designated as a Wetland of International Importance and is rich in biodiversity.1 The study area comes under sub-tropical monsoon climate and yearly rainfall ranges from 982.21 mm to 1980.8 mm. The area experiences rainy season from April to September months. In July month the maximum rainfall is recorded. The mean daily minimum temperature recorded was1°C and maximum temperature recorded was 29°C. 2 There are two types of soil found in Loktak lake and its surrounding areas. They are the Residual poor sandy soil and Transported alluvial soil.3

As one of the most productive and resourceful areas wetlands supply food, non-edible aquatic resources and maintain the ecological balance for the local people and also for the country.4,5 A number of economic, social and ecological benefits are supplied by wetlands.4,5,6 Due to the availability of various types of bioresources people residing around the wetlands are traditionally self-reliant and have subsistence-oriented economy and livelihoods.7 Loktak Lake is considered as the lifeline of the people of Manipur due of its importance in their socio-economic and cultural life. The lake provides ecological and financial security to the people. For their sustenance a large inhabitants residing in the periphery of the lake depends on its resources. 1 Locally known as phumdis (floating islands) are seen in the lake covering with vegetation and is the characteristic feature of the Loktak lake.8 Because of farming practices, urbanization, massive destruction by people, and poorly planned developmental activities wetlands from large portion of the globe have disappeared.9

Around the globe several workers have studied on the utilization of the bioresources of the wetland by the people residing in the periphery and its conservation. Some of those studies are highlighted here. Dahlberg (2005)10 explored competition over natural resources where fibrous plants plays main role to local women who make craftwork for the increasing tourist market through a case study in the Mkuze Wetlands, South Africa, Leima et al., (2008)11 conducted a study to analyze the socio-economic status of the communities residing in six villages situated nearby the Keibul Lamjao National Park, Manipur and their dependence on the park and found that collection of aquatic vegetation from the park, fishing in and around the park contributed to the average annual household income. Rana et al., (2009)7 found that surrounding community in the Hakaluki haor, Bangladesh were dependent on the haor with a different types of income earning activities such as fishing, rearing of duck and cattle, collection of firewood, extraction of sand and collection of reed and the haor was found a poverty stricken region. Singh and Moirangleima (2009)12 reported that the people residing in the periphery of the Loktak lake use the lake for drinking and household uses, hydro-electricity power generation, irrigation, bio-diversity, recreation etc. and the people had undertaken fishing, fish farming, fish marketing, agriculture and ferrying, weaving items of the lake etc. Turyahabwe et al. (2013)13 noted that the role of wetland products to food security and factors influencing utilization of wetland products in Uganda is characterized as food insecure. Bakala et al., (2019)14 also identified that wetlands in Southwestern Ethiopia offer different uses such as livestock grazing, irrigation, recreation, grass and fodder harvest, water supply for livestock and domestic uses, fish harvesting and fuel wood collection but found that they are under pressure due to human activities. Das et al., (2020)15 found that the majority of the inhabitants living around the wetland in Mursidabad, West Bengal (India) by engaging in agriculture or fishing activities are relied on the wetland for their survival and income generation but the health status of the wetland ecosystem were degraded by anthropogenic activities, like high density of population, growth rate of urbanization and density of the road, resulting in the depletion of health of the wetland. Reasonable works relating to the ecology and bioresources of the Loktak lake has been done by workers like Singh and Singh,1994; Singh, 1997; Kosygin and Dhamendra, 2009; Kangabam et al., 2015; Devi and Singh, 2017. 16,17,18,19,20

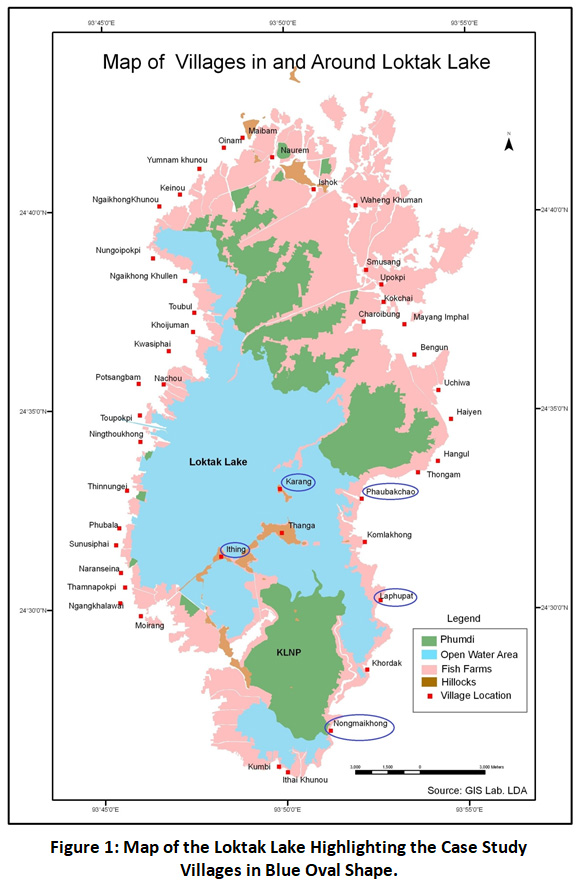

Recently the lake and its ecosystem are degrading because of several anthropogenic pressures. The objective of the present work is to examine different bioresources of the Loktak lake linked to the consumption purpose and household financial earning of the people. The present study on the livelihood dependency on bioresources among the communities residing in the periphery of the lake has been taken up to understand the significance of this lake as an ecological service provider and also generate awareness among the users and the concerned authorities to take up certain steps for sustainable use of the natural resources. The study involved five villages located in and around the Loktak lake i.e., Nongmaikhong, Phoubakchao, Laphupat Tera, Karang and Ithing. The livelihood of the local people of these five villages depended on fishing, collection of prawn, mollusca, mussel, vegetable items, fodder, fuelwood, thatch grasses, medicinal plants and handicrafts materials from the Loktak lake.

Materials and Methods

Table 1 represents the dependence of the five study villages on Loktak lake for livelihood purposes. Around the Loktak lake there are fifty five villages and towns with an overall inhabitants of one lakh. 22 More than ten thousand community residing in the periphery of the lake largely depend on it for their survival and income generation.16 Every fifty five villages depend on the bioresources of the lake either for sustenance or income generation. Among the 55 settlements located in and around the Loktak lake 3 villages i.e. Ithing, Karang and Thanga are island villages and the remaining are lakeshore villages. 5 villages out of 55 were selected purposively for the study as within a limited time frame and resources available it is not possible to cover all the villages around the lake. The villages were also selected purposively for this present study based on their large scale dependency on the lake and also the accessibility of these villages.

Table 1: Respondents (%) Carrying Out Various Activities In and Around Loktak Lake.

|

Activities |

Nongmaikhong |

Phoubakchao |

Laphupat Tera |

Karang |

Ithing |

Mean |

|

Fishing |

95 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

99.0 |

|

Collection of vegetable items |

90 |

100 |

100 |

96 |

26.66 |

82.53 |

|

Collection of water |

75 |

48 |

2.5 |

96 |

100 |

64.3 |

|

Snail collection |

55 |

36 |

32.5 |

0 |

0 |

24.7 |

|

Collection of prawns |

5 |

36 |

60 |

64 |

73.33 |

47.66 |

|

Collection of thatching materials |

30 |

58 |

82.5 |

36 |

6.66 |

42.63 |

|

Collection of handicraft materials |

30 |

18 |

35 |

20 |

0 |

20.6 |

|

Collection of fodder |

0 |

46 |

15 |

0 |

0 |

12.2 |

|

Collection of fuelwood |

85 |

88 |

90 |

88 |

6.66 |

71.53 |

|

Collecting of medicinal plants |

0 |

14 |

30 |

8 |

0 |

10.4 |

|

Collection of oysters |

10 |

0 |

7.5 |

8 |

0 |

5.1 |

|

Collection of eels |

0 |

42 |

50 |

52 |

80 |

44.8 |

|

Boating |

75 |

96 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

94.2 |

|

Bathing |

0 |

14 |

5 |

24 |

33.33 |

15.26 |

Source: Laishram and Dey, 2013 21

|

Figure 1: Map of the Loktak Lake Highlighting the Case Study Villages in Blue Oval Shape. Click here to view Figure |

The 5 villages were chosen following purposive sampling technique considering the objective of this investigation. To conduct an intensive study on the villages and every household and all the family members is difficult within a limited time frame and limited resources available. Hence 25% of households were selected for the study purposively from each of the 5 villages to make a comparison between the villages according to the objective of the study. The households were selected based on their occupational diversity, categorical and religious diversity and their dependency on the Loktak lake for sustenance. The households were chosen to cover the total area of the village. From the selected household the head of the family or any other adult member of the household 20 years of age and above was selected as respondents.

This study is mainly based on the household questionnaire survey with the communities residing in the five selected villages located around the periphery of the Loktak lake. The selected study villages are - 3 lakeshore villages namely Nongmaikhong, Phoubakchao, Laphupat Tera and 2 island villages namely Karang and Ithing. The questionnaire in this study was designed in English and asked in Manipuri, the local language of Manipur. The questionnaire was designed to collect information on the different bioresources of the lake like fishes, prawn, mollusca, mussel, vegetables items, fodders, fuelwoods, thatch grasses, medicinal plants and handicraft materials linked to the livelihood of the people. It also provides background profile of the respondent households like religion, category, educational level, occupation, income and total landholdings.

Purposive sampling technique of about 25% of households 23,24 were conducted resulting in the selection of a total of 300 households. The number of household selected in each village were 40 households were selected from Nongmaikhong village, 100 from Phoubakchao village, 80 from Laphupat Tera village, 50 from Karang village and 30 from Ithing village. The questionnaire sought to obtain information of different bioresources of the Loktak lake linked to the consumption and household financial earning of the people. It was prepared referring 23,25 and in consultation with other relevant literatures. It was pretested and modified to meet the purpose of the study and adapted to suit local conditions of the targeted communities. Specific interviews with intellectual persons of the villages were then conducted and the information collected was verified with the published literatures.16,1

For identification of species the local names and specimen of the bioresources used by the respondents was collected and cross checked with the published literatures26,27,28,29 and identified with the help of experts of Loktak Development Authority (LDA), Manipur. For the correct nomenclature of plant species International Plant Names Index (IPNI) 30 and the Plant List 31 websites were referred. Fish species were identified by using website such as https://www.fishbase.in 32. The data obtained from the survey was compiled and interpreted. Villagewise response percentage and overall percentage of the five villages was calculated for all the questions using Microsoft Excel.

Results and Discussion

In this study a total of 300 respondents were interviewed from the selected households in the five villages. Female respondents were very few in number. Main community in the villages were Hindus followed by Muslims and Christians. Category wise, OBC (Other Backward Class) was found to be the major group for all the villages along with Schedule caste and General population. Most of the respondents were illiterates and very few were Graduates. All of them were fishermen and some were farmers, weavers and small businessmen. Their earnings were found to be low. In the five villages, the highest annual income level was found in the range of “Rs. 30,001 to 60,000/-” and only very few were found earning income level of “Above Rs. 90,000/-”. Maximum number of the respondents have total landholding area in the range of < 1 acre and very few have 2-5 acres of land. The results of the interview as reported by the 300 respondents on the bioresource from the Loktak lake used as food and other bioresources used from the Loktak lake in the five villages are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. In all 38 type of fishes, 1 type of prawn, 2 type of mollusca, 1 type of mussel, 16 type of vegetable items, 8 type of fodders, 6 type of fuelwoods, 3 type of thatch grasses, 12 type of medicinal plants and 2 type of handicraft materials were found used by the people from Loktak lake.

Table 2 presents bioresource from the Loktak lake used as food. In all the five villages fishing was the major activity and a total of 38 species of fishes were found caught from the lake during the study. Overall Monopterus albus (Ngaprum) with 64.33% was caught in highest percentage followed by Labeo rohita (Rohu) with 60.33%. 87.5% of the respondents from Nongmaikhong village caught Monopterus albus (Ngaprum) which was highest. 0.33% of the respondents do not catch fishes from the lake. LDA and WISA (2003) 33 reported 53 types of fishes from the Loktak lake which is more than the present finding.

60% of the respondents were found to collect a prawn species (Macrobrachium dayanum) from the lake. The highest percentage of Macrobrachium dayanum (Khajing) caught from the lake was in Ithing village (86.67%).

Table 2: Bioresource from the Loktak Lake used as Food.

|

Particulars |

|

V1 |

V2 |

V3 |

V4 |

V5 |

Overall |

|

1) Name (type) of fishes used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

|||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1) Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus |

Common carp |

16 (40) |

20 (20) |

21 (26.25) |

5 (10) |

15 (50) |

77 (25.67) |

|

2) Ctenopharyngodon idella (Valenciennes) |

Grass Carp |

24 (60) |

48 (48) |

31 (38.75) |

28 (56) |

16 (53.33) |

147 (49) |

|

3) Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton-Buchanan) |

Mrigal |

8 (20) |

39 (39) |

18 (22.5) |

19 (38) |

15 (50) |

99 (33) |

|

4) Amblypharyngodon mola (Hamilton) |

Muka nga |

9 (22.5) |

63 (63) |

36 (45) |

28 (56) |

15 (50) |

151 (50.33) |

|

5) Trichogaster fasciata Bloch |

Ngabema |

10 (25) |

55 (55) |

34 (42.5) |

34 (68) |

9 (30) |

142 (47.33) |

|

6) Heteropneustes fossilis (Bloch) |

Ngachik |

13 (32.5) |

54 (54) |

29 (36.25) |

17 (34) |

8 (26.67) |

121 (40.33) |

|

7) Clarias nagur (Hamilton) |

Ngakra |

3 (7.5) |

8 (8) |

7 (8.75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

18 (6) |

|

8) Chitala chitala (Hamilton) |

Ngapai |

20 (50) |

39 (39) |

27 (33.75) |

0 (0) |

15 (50) |

101 (33.67) |

|

9) Puntius sophore (Hamilton) |

Phabou nga |

9 (22.5) |

68 (68) |

43 (53.75) |

28 (56) |

13 (43.33) |

161 (53.67) |

|

10) Labeo rohita (Hamilton) |

Rohu |

19 (47.5) |

69 (69) |

37 (46.25) |

34 (68) |

22 (73.33) |

181 (60.33) |

|

11) Hypophthalmichthys molitrix (Valenciennes) |

Silver carp |

9 (22.5) |

27 (27) |

5 (6.25) |

8 (16) |

12 (40) |

61 (20.33) |

|

12) Anabas testudineus (Bloch) |

Ukabi |

25 (62.5) |

54 (54) |

23 (28.75) |

17 (34) |

10 (33.33) |

129 (43) |

|

13) Chanda nama Hamilton |

Ngamhai |

0 (0) |

24 (24) |

36 (45) |

28 (56) |

0 (0) |

88 (29.33) |

|

14) Gagata dolichonema He |

Ngarang |

0 (0) |

17 (17) |

0 (0) |

13 (26) |

0 (0) |

30 (10) |

|

15) Channa striata (Bloch) |

Porom |

13 (32.5) |

60 (60) |

37 (46.25) |

19 (38) |

14 (46.67) |

143 (47.67) |

|

16) Monopterus albus (Zuiew) |

Ngaprum |

35 (87.5) |

51 (51) |

48 (60) |

33 (66) |

26 (86.67) |

193 (64.33) |

|

17) Pethia manipurensis (Menon, Rena Devi, Vishwanath) |

Ngakha Meinganbi |

0 (0) |

7 (7) |

11 (13.75) |

16 (32) |

0 (0) |

34 (11.33) |

|

18) Glossogobius giuris (Hamilton) |

Nylon ngamu |

0 (0) |

14 (14) |

9 (11.25) |

22 (44) |

6 (20) |

51 (17) |

|

19) Notopterus notopterus (Pallas) |

Kandla |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

5 (6.25) |

24 (48) |

0 (0) |

29 (9.67) |

|

20) Mystus bleekeri (Day) |

Ngashep |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

42 (52.5) |

0 (0) |

12 (40) |

54 (18) |

|

21) Wallago attu (Schneider) |

Sareng |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (1.33) |

|

22) Hypsibarbus myithyinae (Prasad & Mukherji) |

Heikak nga |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

15 (18.75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

15 (5) |

|

23) Mystus microphthalmus (Day) |

Nganan |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

7 (8.75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

7 (2.33) |

|

24) Trichogaster labiosus (Day) |

Phetin |

0 (0) |

2 (2) |

25 (31.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

27 (9) |

|

25) Bangana dero (Hamilton) |

Khabak |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

7 (8.75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

7 (2.33) |

|

26) Osteobrama belangeri (Valenciennes) |

Pengba |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

13 (16.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

13 (4.33) |

|

27) Anguilla bengalensis (Gray) |

Ngaril laina |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

13 (16.25) |

0 (0) |

11 (36.67) |

24 (8) |

|

28) Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters) |

Tunghanbi |

4 (10) |

9 (9) |

11 (13.75) |

8 (16) |

2 (6.67) |

34 (11.33) |

|

29) Systomus sarana (Hamilton) |

Ngahou |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

15 (18.75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

15 (5) |

|

30) Mastacembelus armatus (Lacepede) |

Ngaril |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

16 (20) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

16 (5.33) |

|

31) Esomus danricus (Hamilton) |

Ngashang |

0 (0) |

19 (19) |

7 (8.75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

26 (8.67) |

|

32) Catla catla (Hamilton-Buchanan) |

Bao |

0 (0) |

10 (10) |

5 (6.25) |

14 (28) |

3 (10) |

32 (10.67) |

|

33) Bangana devdevi (Hora) |

Ngaton |

0 (0) |

1 (1) |

5 (6.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (2) |

|

34) Labeo gonius (Hamilton) |

Kuri |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (12) |

3 (10) |

9 (3) |

|

35) Osteobrama cotio (Hamilton) |

Ngaseksha |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

5 (6.25) |

0 (0) |

7 (23.33) |

12 (4) |

|

36) Channa punctata (Bloch) |

Ngamu bogra |

11 (27.5) |

36 (36) |

8 (10) |

6 (12) |

9 (30) |

70 (23.33) |

|

37) Lepidocephalichthys guntea (Hamilton) |

Ngakijou |

0 (0) |

4 (4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (1.33) |

|

38) Ompok bimaculatus (Bloch) |

Ngaten |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (1.33) |

|

39) None |

- |

1 (2.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

2) Name (type) of prawns used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

|||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

||||||

|

1) Macrobrachium dayanum Henderson |

Khajing |

7 (17.5) |

57 (57) |

53 (66.25) |

37 (74) |

26 (86.67) |

180 (60) |

|

2) None |

- |

33 (82.5) |

43 (43) |

27 (33.75) |

13 (26) |

4 (13.33) |

120 (40) |

|

3) Name (type) of mollusca used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

|||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

||||||

|

1) Angulyagra oxytropis (Benson) |

Tharoi Ningkhabi |

22 (55) |

26 (26) |

30 (37.5) |

3 (6) |

2 (6.67) |

83 (27.67) |

|

2) Pila globosa (Swainson) |

Labuk tharoi |

22 (55) |

33 (33) |

33 (41.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

88 (29.33) |

|

3) None |

- |

15 (37.5) |

67 (67) |

46 (57.5) |

47 (94) |

28 (93.33) |

203 (67.67) |

|

4) Name (type) of mussels used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

|||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

||||||

|

1) Lamellidens marginalis Lamarck |

Kongreng |

2 (5) |

0 (0) |

3 (3.75) |

2 (4) |

0 (0) |

7 (2.33) |

|

2) None |

- |

38 (95) |

100 (100) |

77 (96.25) |

48 (96) |

30 (100) |

293 (97.67) |

|

5) Name (type) of vegetable items used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

|||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

||||||

|

1) Ludwigia adscendens (L.) H.Hara |

Ishing kundo |

6 (15) |

8 (8) |

27 (33.75) |

17 (34) |

3 (10) |

61 (20.33) |

|

2) Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. |

Kollamni |

22 (55) |

77 (77) |

50 (62.5) |

37 (74) |

9 (30) |

195 (65) |

|

3) Oenanthe javanica (Blume) DC. |

Komprek |

33 (82.5) |

84 (84) |

59 (73.75) |

43 (86) |

13(43.33) |

232 (77.33) |

|

4) Alpinia nigra (Gaertn.) B.L.Burtt |

Pullei |

31 (77.5) |

88 (88) |

58 (72.5) |

38 (76) |

12 (40) |

227 (75.67) |

|

5) Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. |

Thambal |

6 (15) |

1 (1) |

3 (3.75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

10 (3.33) |

|

6) Euryale ferox Salisb. |

Thangjing |

2 (5) |

36 (36) |

6 (7.5) |

17 (34) |

0 (0) |

61 (20.33) |

|

7) Nymphaea pubescens Willd. |

Tharo |

4 (10) |

36 (36) |

19 (23.75) |

18 (36) |

0 (0) |

77 (25.67) |

|

8) Persicaria barbata (L.) H.Hara |

Yellang |

9 (22.5) |

32 (32) |

13 (16.25) |

15 (30) |

0 (0) |

69 (23) |

|

9) Trapa natans L. |

Heikak |

7 (17.5) |

24 (24) |

19 (23.75) |

18 (36) |

1 (3.33) |

69 (23) |

|

10) Hedychium coronarium J.Koenig |

Loklei |

20 (50) |

89 (89) |

59 (73.75) |

38 (76) |

13(43.33) |

219 (73) |

|

11) Zizania latifolia (Griseb.) Turcz. ex Stapf |

Ishing Kambong |

0 (0) |

22(22) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

22 (7.33) |

|

12) Vigna grandiflora (Prain) Tateishi & Maxted |

Phum hawai |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

11 (13.75) |

4 (8) |

1 (3.33) |

16 (5.33) |

|

13) Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott |

Pangkhok |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

10 (20) |

3 (10) |

13 (4.33) |

|

14) Polygonum perfoliatum L. |

Lilhar |

2 (5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.67) |

|

15) Alocasia cucullata (Lour.) G.Don |

Singjupan |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (2.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.67) |

|

16) Neptunia oleracea Lour. |

Ishing ekaithabi |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (1.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

17) None |

- |

2 (5) |

5 (5) |

17 (21.25) |

4 (8) |

17(56.67) |

45 (15) |

Numbers inside the brackets represent the percentage of the particular bioresource collected

V1= Nongmaikhong, V2=Phoubakchao, V3= Laphupat Tera, V4=Karang, V5=Ithing

Overall, 2 species of freshwater mollusca i.e. 29.33% of Pila globosa (Labuk tharoi) and 27.67% of Angulyagra oxytropis (Tharoi Ningkhabi) were found to be used by the respondents. The highest percentage of both the species of molluscas i.e. Angulyagra oxytropis (Ningkhabi) and Pila globosa (Labuk tharoi) was collected in Nongmaikhong village which was 55% each. 67.67% of the respondents does not used mollusca. As observed by Kumar (2013)34 for supply of water, for the supply of water to land or crops, for household uses, catching fishes, catching of migratory waterbirds for sale, for wild rice collection and edible invertebrate, Pila globosa and plant product which are edible such as Singhada (water chestnut), Makhana (foxnut) the Kabartal wetland has been used.

Overall 2.33% of the respondents collected 1 species of mussel i.e. Lamellidens marginalis (Kongreng) and 97.67% of the respondents did not use mussels. The highest percentage of collection was found in Nongmaikhong village (5%).

It is seen from the above that in some villages mollusca and mussels were not collected as they were considered as secondary items in comparison with other resources mainly fishes and vegetable items which provides them with more self sustenance and higher income generation. Besides, species of mollusca and mussels are degrading from the part of the lake adjoining the villages.

16 species of vegetable items were used by the respondents. Overall, Oenanthe javanica (Komprek) with a percentage of 77.33%, Alpinia nigra (Pullei) (75.67%), Ipomoea aquatica (Kollamni) (65%) etc. were the most harvested vegetables. Among all vegetables Hedychium coronarium (Loklei) was harvested in highest percentage (89%) in Phoubakchao village. 15% of the respondents did not use any vegetable items. Singh (2002) 35 also identified 54 species of plants available on the Phumdis of Loktak lake, Manipur, India having importance to the local people for their livelihood and were found to be used for edible, cultural, medicinal, fodder, house making and biofertilizer purposes.

Table 3: Other Bioresources used from the Loktak Lake.

|

Particulars |

V1 |

V2 |

V3 |

V4 |

V5 |

Overall |

|

|

|

1) Name (type) of fodders used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

|

|||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

|

||||||

|

1) Echinochloa stagnina (Retz.) P.Beauv. |

Hup |

0 (0) |

22 (22) |

10 (12.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

32 (10.67) |

|

|

2) Zizania latifolia (Griseb.) Turcz. ex Stapf |

Ishing Kambong |

0 (0) |

27 (27) |

9 (11.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

36 (12) |

|

|

3) Alternanthera philoxeroides (Mart.) Griseb. |

Kabonapi |

0 (0) |

3 (3) |

1 (1.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (1.33) |

|

|

4) Panicum notatum Retz. |

Wanamanbi |

0 (0) |

20 (20) |

8 (10) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

28 (9.33) |

|

|

5) Ludwigia sassiliflora Roven |

Chaoradevo |

0 (0) |

2 (2) |

1 (1.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (1) |

|

|

6) Oryza rufipogon Griff. |

Wainu chara |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (3.75) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (1) |

|

|

7) Jussiaea suffruticosa L. |

Tebo |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (1.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

|

8) Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. |

Phungpai |

0 (0) |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

|

9) None |

- |

40 (100) |

69 (69) |

70 (87.5) |

50 (100) |

30 (100) |

259 (86.33) |

|

|

2) Name (type) of fuelwoods used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

|

|||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

|

||||||

|

1) Saccharum arundinaceum Retz. |

Singnang |

3 (7.5) |

14 (14) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

17 (5.67) |

|

|

2) Phragmites karka (Retz.) Trin. ex Steud. |

Tou |

31 (77.5) |

92 (92) |

60 (75) |

38 (76) |

4 (13.33) |

225 (75) |

|

|

3) Saccharum narenga (Nees ex Steud.) Hack. |

Singmut |

4 (10) |

16 (16) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

20 (6.67) |

|

|

4) Saccharum spontaneum L. |

Khoimom |

19 (47.5) |

87 (87) |

60 (75) |

39 (78) |

4 (13.33) |

209 (69.67) |

|

|

5) Quercus lamellose Sm. |

Uyung |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

6 (7.5) |

0 (0) |

1 (3.33) |

7 (2.33) |

|

|

6) Mitragyna diversifolia (Wall. ex G.Don) Havil. |

Chomlang |

0 (0) |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

|

7) None |

- |

7 (17.5) |

6 (6) |

20 (25) |

11 (22) |

26 (86.67) |

70 (23.33) |

|

|

3) Name (type) of thatch grasses used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

||||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

|||||||

|

1) Zizania latifolia (Griseb.) Turcz. ex Stapf |

Ishing Kambong |

18 (45) |

44 (44) |

44 (55) |

16 (32) |

1 (3.33) |

123 (41) |

|

|

2) Imperata cylindrica (L.) Raeusch. |

Ee |

2 (5) |

47 (47) |

20 (25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

69 (23) |

|

|

3) Chrysopogon zizanioides (L.) Roberty |

Tumnou |

0 (0) |

2 (2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.67) |

|

|

4) None |

- |

21 (52.5) |

47 (47) |

35 (43.75) |

34 (68) |

29 (96.67) |

166 (55.33) |

|

|

4) Name (type) of medicinal plants used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

||||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1) Stephania glabra (Roxb.) Miers |

Koubruyai |

0 (0) |

18 (18) |

24 (30) |

1 (2) |

1 (3.33) |

44 (14.67) |

|

|

2) Crassocephalum crepidioides (Benth.) S. Moore |

Tera paibi |

1 (2.5) |

2 (2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.67) |

|

|

3) Mukia maderaspatana (L.) M.Roem. |

Lamthabi |

0 (0) |

5 (5) |

1 (1.25) |

3 (6) |

1 (3.33) |

10 (3.33) |

|

|

4) Nymphoides indica (L.) Kuntze |

Yelli/Thariktha-macha |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (2) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

|

5) Tinospora sinensis (Lour.) Merr. |

Ningthoukhonglei |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (2) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

|

6) Neptunia oleracea Lour. |

Ishing ekaithabi |

0 (0) |

2 (2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.67) |

|

|

7) Ludwigia adscendens (L.) H. Hara |

Ishing kundo |

0 (0) |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

1 (2) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.67) |

|

|

8) Eclipta prostrata (L.) L. |

Uchi sumban |

0 (0) |

4 (4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (1.33) |

|

|

9) Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn |

Laichangkhrang |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (1.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

|

10) Knoxia roxburghii (Spreng.) M. A. Rau |

Meeitei lembum |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

4 (1.33) |

|

|

11) Alpinia nigra (Gaertn.) B. L. Burtt |

Pullei |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (1.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

|

12) Leucas lavandulifolia Sm. |

Mayanglemboom |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (1.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.33) |

|

|

13) None |

- |

39 (97.5) |

80 (80) |

55 (68.75) |

46 (92) |

29 (96.67) |

249 (83) |

|

|

5) Name (type) of handicraft materials used from the lake (Scientific and Local name) |

||||||||

|

Scientific name |

Local name |

|||||||

|

1) Schoenoplectus lacustris (L.) Palla |

Kouna |

12 (30) |

23 (23) |

25 (31.25) |

4 (8) |

0 (0) |

64 (21.33) |

|

|

2) Cyperus alternifolius L. |

Chumthang |

2 (5) |

19 (19) |

26 (32.5) |

9 (18) |

0 (0) |

56 (18.67) |

|

|

3) None |

- |

28 (70) |

76 (76) |

52 (65) |

38 (76) |

30 (100) |

224 (74.67) |

|

Numbers inside the brackets represent the percentage of the particular bioresource collected

V1= Nongmaikhong, V2=Phoubakchao, V3= Laphupat Tera, V4=Karang, V5=Ithing

Table 3 presents other bioresources used from the Loktak lake. Eight species of fodders were found used by the respondents. In all the five villages together Zizania latifolia (Ishing Kambong) (12%), Echinochloa stagnina (Hup) (10.67%) and Panicum notatum (Wanamanbi) (9.33%) etc. were collected in highest percentages. 86.33% of the respondents did not use fodders. Among the villages, Zizania latifolia (Ishing Kambong) (27%) was collected in highest percentage in Phoubakchao village. The important fodder plant species used from the Loktak lake were Hedychium coronarium, Alpinia nigra, Oryza rufipogon and Zizania latifolia.36

Six species of fuelwoods were collected from the lake. Phragmites karka (Tou) and Saccharum spontaneum (Khoimom) were collected in higher percentage i.e. 75% and 69.67% respectively. 23.33% of the respondents did not collect any fuelwoods. These villagers purchased firewood from the local market and some of them have LPG (Gas) connection for cooking purposes. Phragmites karka (Tou) with a percentage of 92% in Phoubakchao village was collected in highest percentage among all the 6 species. Pramod et al., (2015)37 also reported that the major wetland resources being extracted from Ghodaghodi Lake, Western Nepal were fuelwood, fodder, fish, singar, and sal leaf.

Three species of thatch grasses were collected by the respondents. In the overall percentage of the species of thatch grasses collected from the lake Zizania latifolia (Ishing Kambong) with 41% was found highest followed by Imperata cylindrica (Ee) with (23%). 55.33% of the respondents did not collect any thatch grasses. Zizania latifolia (Ishing Kambong) was collected in highest percentage in Laphupat Tera village (55%). Devi et al., (2014)38 reported that Cymbopogon citrates, Imperata cylindrica, Phragmites karka, Saccharum arundinaceum and Saccharum procerum collected from Loktak lake were used as thatching, fodder and fuel materials.

Twelve species of medicinal plants were found used by the respondents. In the overall percentage of the species of medicinal plants collected from the lake Stephania glabra (Koubruyai) with 14.67% was found highest. 83% of the respondents did not collect any medicinal plants. Stephania glabra (Koubruyai) was collected in highest percentage in Laphupat Tera village (30%). The collected medicinal plants were used for the treatment of health disorders such as fever, swelling, boil, jaundice, typhoid, mouth ulcer, diabetes and lack of blood etc. Panda and Misra (2011)39 found that 48 wetland plants under 40 genera and 23 families were used by the local people against 47 ailments.

Two species of handicraft materials i.e. Schoenoplectus lacustris (Kouna) and Cyperus alternifolius (Chumthang) were found collected by the respondents for making mats. In all the five villages it was found that Schoenoplectus lacustris (Kouna) with a percentage of 21.33% was found collected highest followed by Cyperus alternifolius (Chumthang) (18.67%). 74.67% of the respondents did not collect any handicraft materials. Collection of handicraft material like Cyperus alternifolius (Chumthang) was highest (32.5%) in Laphupat Tera village. Singh (2002)40 also reported that plants like Cyperus spp. and Scirpus lacustris collected from the Loktak lake were used for mat formation.

For sustenance and household earnings fishes like Monopterus albus, Labeo rohita, Puntius sophore, Amblypharyngodon mola etc, prawn like Macrobrachium dayanum, mollusca like Angulyagra oxytropis, Pila globosa, vegetables like Oenanthe javanica, Alpinia nigra, Hedychium coronarium etc. were collected from the lake and sold in the nearby market. Singh (2002)40 also reported that plants like Alpinia galanga, Hedychium coronarium, Trapa natans, Oenanthe javanica etc. were very important for household income generation and people living in the lakeshore of the Loktak lake collected these plants and sold in the market earning around Rs.100 per day. For household purposes fodders, fuelwoods, thatch grasses, medicinal plants and handicraft materials collected from the Loktak lake were mainly used.

Recently, resources of the Loktak lake are degrading due to the rising dependency of human on the lake, haphazard agricultural practices (run-off from fertilizers and pesticides from agricultural fields into the lake), contamination of water (due to discharge of wastes from municipal areas, fertilizers and pesticides from crop fields, washing of clothes and utensils, bathing), siltation from different inlets of the catchment areas resulting in the depletion of bioresources, building of Ithai dam and maintaining of high water level of Loktak Lake leading to disappearance of the fishes and loss of natural fishery because of fishes migration, encroachments in the lake by constructing fishponds, construction of roads and settlements etc. (leading to more settlement of people in floating islands (phumdis) and thereby overharvesting the bioresources of the lake). Laishram and Dey (2014)41 noted that the readings of water quality parameters like DO (8.58 mg/l ) and BOD (5.07 mg/l) of the Loktak lake were higher than the World Health Organization (WHO) standard limits which showed that moderate water pollution of Loktak lake took place due to release of municipal sewage, domestic wastes, fertilizers and pesticides from agricultural practices. Khwairakpam et al., (2021)42 observed that due to river run-off from sub-catchments carrying sewage loads, soil sediments and agricultural fertilizers the Loktak lake is polluting.

In the present investigation it is also observed that all the villages are found to depend on the bioresources of the Loktak lake equally irrespective of the community or caste, category, educational level, occupation, income of the villagers. Since all the communities depended on the lake equally no variation in dependency based on community or caste, category, educational level, occupation, income is observed in this study. Dependency of the people on Loktak lake is for various purposes like food, fodder, fuelwood, building of houses, medicinal purposes and for handicraft. Fodders, fuelwoods, thatch grasses, medicinal plants and handicraft materials were found used by the villagers for household purpose. Fishing is the most important occupation of the people of the villages surveyed. Species of fishes like Labeo rohita, Cyprinus carpio, Ctenopharyngodon idella and Cirrhinus mrigala etc, prawn like Macrobrachium dayanum, mollusca like Angulyagra oxytropis, Pila globossa, mussel like Lamellidens marginalis, vegetables like Persicaria barbata, Zizania latifolia, Nelumbo nucifera, Euryale ferox, Alpinia nigra, Hedychium coronarium etc. were collected from the lake for selling purpose and have been sold in the local market with good income generation.

Conclusion

In this investigation high dependency on Loktak lake by those people residing in and around it for consumption purpose and household financial earning were noted but because of certain human activities the lake was found to be polluted and destruction of the surrounding natural environment occurred all these result in poor socio-economic condition of the community. It can be concluded that the local people residing in the five study villages which lies in the periphery of the Loktak lake were found to be poor and along with low educational level and small income. They depended on the lake’s resources such as fishes, vegetable items, fuelwood, mollusca, mussel, prawn, fodder, thatching, handicrafts materials and medicinal plants for their livelihood and income generation. From the household survey it was found out that the resources in which the livelihood of the people depended are degrading day by day and some resources has been responded to be lost from the lake. Some species of the resources like fish, vegetable item, fodder, fuelwood, thatch grass, medicinal plant and handicraft materials has also been responded to be degrading or lost from some of the villages.

Degradation or lost of resources from the lake not only directly affect the livelihood and income generation of the people depending on it but also causes destruction of the surrounding environment. Hence, for the protection and long term management of the Loktak lake and the resources of the lake it can be suggested to improve the literacy level in the villages and introduce more provision of higher education facilities which will make the communities eligible for getting government or private jobs resulting in less dependency on the bioresources of the Loktak lake. Alternative means of sustenance by encouraging villagers in culture fisheries, handloom and handicrafts, food processing etc. can be introduced.

In 1986 for the overall improvement and management of the Lake the Government of Manipur established Loktak Development Authority (LDA). For the conservation and protection of the Loktak lake this authority has been working by adopting several good policies. Phumdi management, water management, catchment conservation, biodiversity conservation, sustainable resource development and livelihood improvement, communication, education, participation and awareness, monitoring and evaluation, etc. are being taken up by this organization. Developing an interest among the people to take part in the conservation and sustainable management of Loktak lake by involving the local people in lakeshore villages and organizing more effective conservation-related programmes etc. by the concerned authorities can be taken up. The anthropogenic activities around the lake should be control for the overall conservation of the lake. More documentation on the recent status of the bioresources of the Loktak lake so as to attract the attention of the concerned authorities for conservation of the lake should be taken up. Effective enforcement and implementation of laws will help in the overall protection, conservation, management, restoration and development of the Loktak lake and its resources for recent and upcoming generations

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the Project Director, Loktak Development Authority (LDA), Imphal for granting permission to carry out this study. Author is also thankful for the village authorities and local guides who helped in conducting the household survey and gratefully acknowledged those respondents who spared their valuable time during the survey and shared vital information.

Funding Source

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The author does not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Trisal, C.L., and Manihar, T.H. The Atlas of Loktak lake. Wetlands International and Loktak Development Authority, New Delhi; 2004.

- Singh, R.N., Singh, N.S., Garg, J.K.., and Murthy, T.V.R. Loktak Notified Wetland Ecosystem and its Catchment. In: Singh, R.K.., and Sharma, H.P. Wetlands of Manipur. (Vol-1). Manipur Association for Science & Society (MASS), Imphal;1999: Pages numbers 43-52.

- Singh, T.H. N. Loktak and its Environment in Manipur. Rajesh publications, New Delhi; 2010.

- Dugan, P.J. Wetland Conservation: A Review of Current Issues and Required Action. In: Nishat, A., Hussain, Z., Roy, M.K., and Karim, A. Freshwater Wetlands in Bangladesh: Issues and Approaches for Management. IUCN-The World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland; 1990: Page numbers 45-53.

- IWRB (International Waterfowl and Wetlands Research). Action Programme for the Conservation of Wetlands in South and West Asia. In: Nishat, A., Hussain, Z., Roy, M.K., and Karim, A. Freshwater Wetlands in Bangladesh: Issues and Approaches for Management. IUCN- The World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland; 1992: Page numbers 112-119.

- Khan, M.S, Haq, E, Huq, S, Rahman, A.A, Rashid, S.M.A, Ahmed, H. Wetlands of Bangladesh. Holiday Printers Ltd., Bangladesh; 2009.

- Rana MP, Chowdhury MSH, Sohel MSI, Akhter S and Koike M. 2009. Status and socio-economic significance of wetland in the tropics: a study from Bangladesh. Forrest, 2:172-177.

CrossRef - Trisal, C.L., and Manihar, T.H. Management of Phumdis in the Loktak Lake. In: Trisal, C.L., and Manihar, T.H. Proceedings of a workshop on Management of Phumdis in Loktak Lake, January 22-24, 2002. Wetlands International-South Asia, New Delhi and Loktak Development Authority, Manipur, India; 2002: Page numbers 1-6.

- Kabii, T. An overview of African wetlands. In: Hails, A.J. Wetlands biodiversity and the Ramsar convention, Ramsar Convention Bureau, Gland, Switzerland; 1996: Page numbers 69-75.

- Dahlberg A. 2005. Local resource use, nature conservation and tourism in Mkuze wetlands, South Africa: A complex weave of dependence and conflict. Danish Journal of Geography, 105(1):43-55.

CrossRef - Leima, T.S., Pebam, R., and Hussain, S.A . Dependence of lakeshore communities for livelihood on the floating islands of Keibul Lamjao National Park, Manipur, India. In: Sengupta, M., and Dalwani, R. Proceedings of Taal 2007: The 12th World Lake Conference, Jaipur; 2008: Page numbers 2088-2090.

- Singh AL and Moirangleima K. 2009. Shrinking Water Area in the Wetlands of the Central Valley of Manipur. The Open Renewable Energy Journal, 2:1-5.

CrossRef - Turyahabwe N, Kakuru W, Tweheyo M and Tumusiime DM. 2013. Contribution of wetland resources to household food security in Uganda. Agriculture & Food Security, 2(5):1-12.

CrossRef - Bakala F, Alemkere A and Tolossa T. 2019. Socioeconomic Importance of Wetlands in Southwestern Ethiopia: Evidences from Bench-Maji and Sheka Zones. Journal of Ecology & Natural Resources, 3:1-8.

- Das S, Pradhan B, Shit PK and Alamri A M. 2020. Assessment of Wetland Ecosystem Health Using the Pressure–State–Response (PSR) Model: A Case Study of Mursidabad District of West Bengal (India). Sustainability, 12:1-18.

CrossRef - Singh, H. T., and Singh, R.K.S. Loktak lake, Manipur. World Wide Fund for Nature, India, New Delhi; 1994.

- Singh KS. 1997. Ecology of the Loktak lake of Manipur and its Floating Phoom Hut Dwellers. Journal of Human Ecology, 6: 255-259.

- Kosygin, L., and Dhamendra, H. Ecology and conservation of Loktak lake, Manipur: An overview. In: Kosygin, L. Wetlands of North East India: Ecology, Aquatic Bioresources and Conservation. Akansha Publishing House, New Delhi; 2009: Page numbers 1-20.

- Kangabam RD, Boominathan SD and Govindaraju M. 2015. Ecology, disturbance and restoration of Loktak Lake in Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot- An overview. NeBIO, 6: 9-15.

- Devi MH and Singh P K. 2017. Flowering Calendar of the Macrophytes of Keibul Lamjao National Park, Loktak Lake, Manipur, India. Research Journal of Botany, 12: 14-22.

CrossRef - Laishram J and Dey M. 2013. Socio-Economic Condition of the Communities Dependent on Loktak Lake, Manipur: A Study on Five Lakeshore Villages. International Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 39(2):87-96.

- LDA (Loktak Development Authority) and WISA (Wetlands International-South Asia). Loktak Newsletter. Vol-1. Loktak Development Authority, Imphal and Wetland International-South Asia, New Delhi; 1999.

- Sah JP and Heinin JT. 2001. Wetland resource use and conservation attitudes among indigenous and migrant peoples in Ghodaghodi Lake area, Nepal. Environmental Conservation, 28(4):345-356.

CrossRef - Shrivastava RJ and Heinen JT. 2007. A Microsite Analysis of resource use around Kaziranga National Park, India (Implications for Conservation and Development Planning). The Journal of Environment and Development, 16(2):207-226.

CrossRef - Baral N and Heinen JT. 2007. Resource use, conservation attitudes, management intervention and park-people relations in the Western Terai landscape of Nepal. Environmental Conservation, 1-9.

CrossRef - Sinha, S.C. Medicinal plants of Manipur, Manipur Association for Science & Society (MASS), Imphal; 1996.

- Singh, N.P., Chauhan, A.S., and Mondal, M.S. Flora of Manipur. Vol.I. Botanical Survey of India, Calcutta; 2000.

- Jayaram, K. C. The freshwater fishes of the Indian region. Narendra Publishing House, Delhi, India; 2010.

- Vishwanath, W., Nebeshwar, K., Lokeshwor, Y., Shangningam, B.D., and Rameshori, Y. Freshwater fish taxonomy and a manual for identification of fishes of Northeast India. National Workshop on freshwater fish taxonomy. Dept. of Life Science, Manipur University. National Bureau of Fish Genetic Resources, Lucknow; 2014.

- International Plant Names Index. http://www.ipni.org. Accessed on September 17, 2020.

- The Plant List. http://www.theplantlist.org. Accessed on September 20, 2020.

- FishBase. https://www.fishbase.in. Accessed on October 3, 2020.

- LDA (Loktak Development Authority) and WISA (Wetlands International-South Asia). Loktak Newsletter. Vol-3. Loktak Development Authority, Imphal and Wetland International South Asia, New Delhi; 2003.

- Kumar M. 2013. Resource inventory analysis of Kabartal wetland. International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(8):13-26.

- Singh, P.K. Some ethnobotanically important plants available on the Phumdis of Loktak lake. In: Trisal, C.L., and Manihar, T.H. Proceedings of a workshop on Management of Phumdis in Loktak Lake, January 22-24, 2002. Wetlands International-South Asia, New Delhi and Loktak Development Authority, Manipur, India; 2002: Page numbers 37-42.

- Devi MH, Salam JS, Joylani SD, Singh PK and Choudhury MD. 2013. Biochemical Study of Ten Selected Fodder Plants of Critically Endangered Sangai (Rucervus eldii eldii Mc Clelland). Env. Ecol., 31(2): 573 -581.

- Pramod L, Krishna PP, Lalit K and Kishor A. 2015. Sustainable livelihoods through conservation of wetland resources: a case of economic benefits from Ghodaghodi Lake, Western Nepal. Ecology and Society, 20:1-11.

CrossRef - Devi MH, Singh PK and Choudhury MD. 2014. Income-generating plants of Keibul Lamjao National Park, Loktak Lake, Manipur and man-animal conflicts. Pleione, 8(1): 30-36.

- Panda A and Misra MK. 2011. Ethnomedicinal survey of some wetland plants of South Orissa and their conservation. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 10(2):296-303.

- Singh S.S. Vegetation and phumdi of Keibul Lamjao National Park. In: Trisal, C.L. and Manihar, T.H.. Proceedings of a workshop on Management of Phumdis in Loktak Lake, January 22-24, 2002. Wetlands International-South Asia, New Delhi and Loktak Development Authority, Manipur, India; 2002: Pages numbers 29-36.

- Laishram J and Dey M. 2014. Water Quality Status of Loktak Lake, Manipur, Northeast India and Need for Conservation Measures: A Study on Five Selected Villages. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 4(6):1-5.

- Khwairakpam E, Khosa R, Gosain A and Nema A. 2021. Water quality assessment of Loktak Lake, Northeast India using 2-D hydrodynamic modelling. SN Applied Sciences, 3:422.

CrossRef